It’s raining mulberries on our dinner table at the Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasa in Bukhara, an ancient city on the Silk Road in Uzbekistan, Central Asia.

The trunks of trees in Uzbekistan are all painted white to protect from infestation – this white mulberry tree in the madrasa was directly above our table

They’re white mulberries, also known as silkworm mulberries (

Morus alba), not the black ones which stain your fingers and clothes. Their leaves feed silkworms, those voracious little spinners whose fibres were coveted for thousands of years by Greeks, Romans and Persians.

In his fascinating book,

A Carpet Ride to Khiva, Christopher Aslan Alexander says that the secret of silk was discovered accidentally around 4500 years ago by the Yellow Empress of China.

“She was reputedly enjoying a bowl of green tea in her garden when a cocoon plopped into her cup from the overhanging mulberry tree. She tried to fish it out and it began to unravel – changing the fortune of her empire in the process. Not only did silk provide a warm, comfortable fibre for making into cloth, it also possessed a unique luminescence and lustre that made it the queen of fabrics.”

Enjoying ice cream under an ancient mulberry tree alongside the Lyabi-Hauz, or Holy Pool, in the centre of the old city. The Divan Begi Madrasa overlooks the pool

A few fall into the small dishes set out to tempt us before the main meal. They include tiny cheese pastries, yoghurt, orange & kiwi fruit segments, a beetroot salad and the ubiquitous tomato & cucumber salad.

Alas, no cocoons, though a fashion parade of traditional silk evening gowns, complete with gold embroidery and modelled by stylish young women, is taking place before our eyes in the courtyard.

The haunting sounds of the Ud and ghijjak, an instrument similar to the violin, are playing in the background, accompanied by the tanbur (a long-necked string instrument) rubab (lute-like instrument) and doira (drum).

Our main course arrives in a small hot terracotta pot. There are thickly sliced carrots on top, then a layer of potatoes followed by a layer of tomatoes and pieces of fatty mutton at the bottom. The meat is chewy and leaves a strong aftertaste of lamb fat.

Terracotta pot with layers of carrots, potatoes, tomatoes and fatty mutton, a typical Uzbek dish (as one travel guide puts it, Uzbekistan is the artery-clogged heart of Central Asia)

Admittedly my reasons for visiting this fascinating part of the world weren’t to do with food, though I would have appreciated more meals in the homes of local people to sample true

Uzbek cooking, such as the

plov made by Rakhmon Toshev one night.

Rather, I was motivated by a tour my mother did in 2006 with the late Dee Court, (stylist

Sibella Court is her daughter), who was working at the time with

Alumni Travel and whose knowledge of the history, architecture, carpets and textiles of Uzbekistan was outstanding.

I was also keen to set foot in Bukhara and Samarkand, two legendary cities mentioned by Gurdjieff in his book

Meetings with Remarkable Men. Gurdjieff was

an influential Greek-Armenian spiritual teacher last century who travelled to Central Asia in search of the “truth”. The men – or “seekers of truth” – whom he met on his travels helped him track down ancient spiritual masters and texts from which he went on to develop “The Work”.

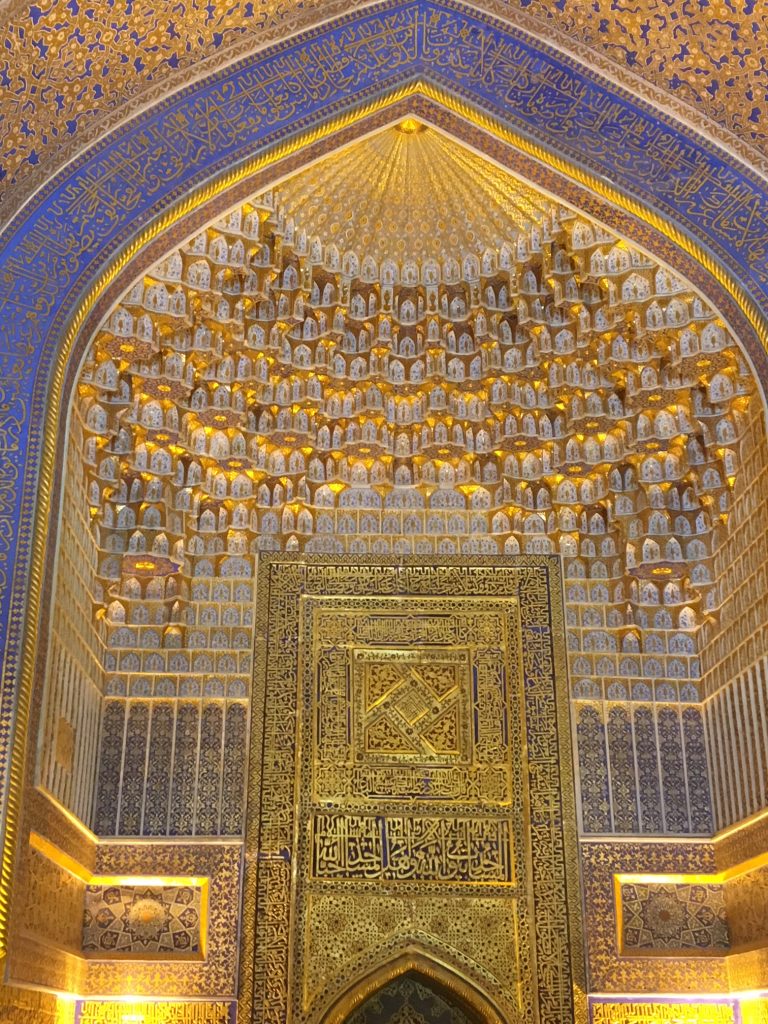

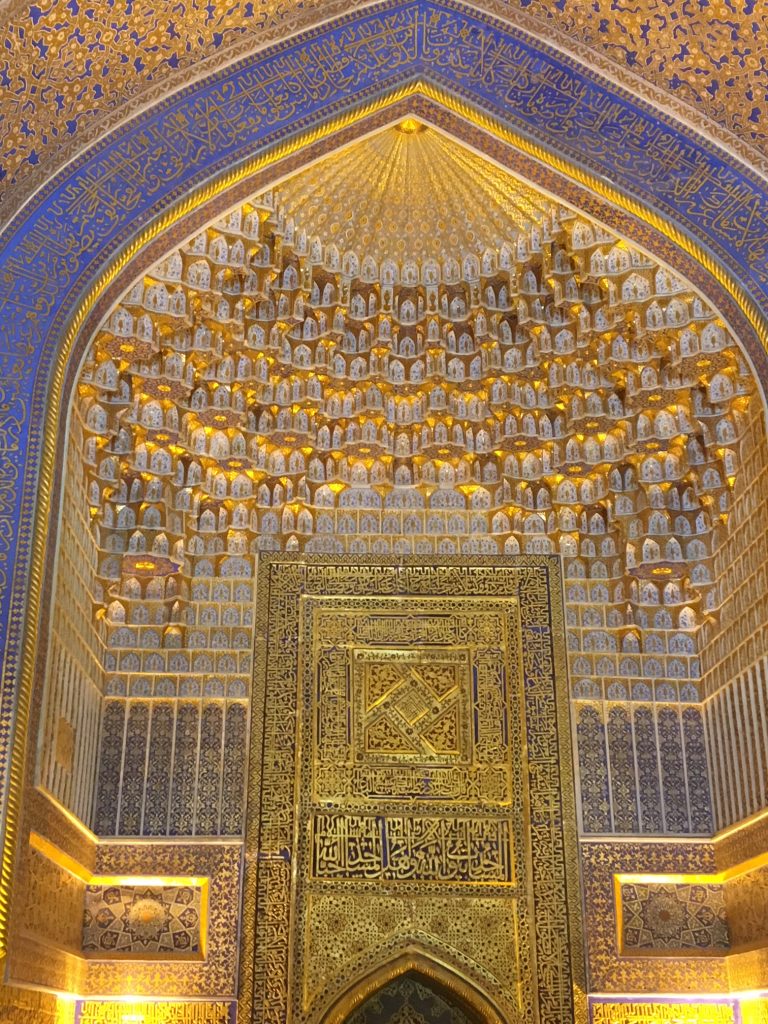

Cornice of the stunning gilded ceiling of the Tilla Kari Madrassa, part of the Registan complex in Samarkand – more than 4kg of gold leaf was used to decorate the ceiling

As John Lawton observes in

Travel to Landmarks: Samarkand and Bukhara, few landmarks have tantalised the minds of men more than the legendary caravan cities of Central Asia.

“For the lust of knowing what should not be known,” wrote British poet-diplomat James Elroy Flecker,“we make the Golden Journey…to divine Bukhara and happy Samarkand.”

Gilded interior of the Tilla-Kari Mosque decorated with gold to symbolise Samarkand’s wealth at the time it was built

Until recently, few Westerners had visited these remote inaccessible cities hidden behind mountains and deserts, though many (including Keats, Milton, Marlowe, Kipling and Oscar Wilde) had written about them, but not set foot there.

One Westerner who reached Bukhara in the 13th century was Marco Polo who described it as a “city most noble and grand.” Another was Lord Curzon in the 19th century who found it in decline but still “the most interesting city in the world.”

Once the holiest city in Central Asia, it was said that the light in Bukhara shone up to heaven, not down, and still today – despite decimation by Genghis Khan in 1220 and the Soviets in the 1920s – it remains one of the most esteemed cities in Islamic civilization. The name Bukhara is related to the Sanskrit

vihara (shrine or monastery) while the Zoroastrian Magi translated Bukhara as

temple.

Mind you, my initial impression of Bukhara was somewhat disappointing and almost quenched my lust. We’d taken the Afrosiyob fast train from Samarkand which sped us across a dry sandy plain to Bukhara’s modern railway station, situated 12km from the old city.

The Afrosiyub fast train, named after a mythical king, which offers excellent service (including tea, coffee, sandwiches, snacks )

I was astonished by the amount of traffic on the road leading to the old city and by the vast number of sandy-coloured apartments being built on each side. We passed a big soccer stadium and a large

Bella Italia restaurant before being told the road was blocked and we’d have to walk in to the old city where we encountered more building work taking place in the old alleyways.

Under the mulberry tree: Restaurant old Bukhara

It was a hot windy day and I was delighted to stumble across the

Restaurant Old Bukhara restaurant, situated in a cool shady courtyard not far from the Lyabi-Hauz plaza in the centre of the old city.

Their

mastava, a traditional Uzbek soup made with meat, rice and vegetables and served with sour cream was flavoursome, but I really enjoyed their beef kebabs (or

shashlyk), fresh from the charcoal brazier and served with thinly sliced onion rings.

Mouthwatering kebabs straight from the grill, Restaurant Old Bukhara

Meat kebabs are popular throughout Central Asia, be they beef, marinated mutton, chicken, minced meat or vegetables and vary in quality – minced meat kebabs can be rather fatty while mutton kebabs are often chewy.

Fresh meat samosas from a roadside mud tandoor oven

One of the other welcome surprises in Bokhara were the freshly cooked meat samosas (

samsas) which we stumbled across at a roadside tandoor on our way to the Bolo Hauz mosque.

Bolo Hauz Mosque, built in 1712- its carved wooden pillars and vaulted iwan are magnificent

The following day I came across a local woman in the old city selling piping hot vegetable samosas from a tray.

Vegetable samosas for sale near a shop selling suzani (silk embroidery) under one of the trading domes

But the most impressive meal I had was the one at the Rakhmon’s home restaurant, tucked away in an alley not from

Sasha & Sons B&B, where the family has a magnificent

suzani (silk embroidery) workshop. Here we were introduced to the delightful

Nasiba whose father

Rakhmon Toshev is a

suzani and

plov master.

While Nasiba explained how the

suzanis are made (the fabrics, threads, patterns and dyes used), her father busied himself outside over an enormous cast iron pot making a large quantity of

plov Emir.

Checking the meat and vegetable layers under the rice before adding water and putting the lid back on

Starting with the large pieces of meat (beef or lamb, chicken is rarely used in Bukhara) which are browned in cottonseed oil, he added a layer of onion, then carrot, raisins, whole garlic bulbs and spices which included black and white cumin seeds, coriander seeds, smashed cardamom, cloves, barberry, saffron, dill seed, muscat, black pepper and sweet paprika, and then long grain rice (250ml-500ml oil:1Kg rice!). Holes were made in the top of the rice to add boiling water, a lid was set on top and then water thrown over the wood fire to lower the temperature and infuse the

plov with wood smoke.

The colourful festive “plot Emir” (fit for a king) decorated with quail eggs

It was a busy night with many guests and I really enjoyed the warm family atmosphere. His dedication to making this colourful festive dish parallels his dedication to embroidering

suzani which Nasiba told me he does in winter.

“He prefers to work in silence when there’s no-one around and will often sit for 12 hours so that he can put his heart into it. My mother sits alongside him.”

My favourite

suzani was the silk one of the three phoenix embroidered by him and with a sale price of $10,500, sadly well beyond my budget.

Rakhmon Toshev’s magnificent silk suzana with three phoenix

It

reminded me of the stunning pair of phoenix facing each other on the facade of the Divan Begi Madrasa where we’d dined the night before – mythic birds which symbolise the rise and fall of this holy city over the millennia.

The facade of the Divan Begi Madrasa: one of the finest examples of figurative tilework in Uzbekistan – a pair of phoenix facing each other on either side of a sun with a human face (which directly contravenes the Islamic prohibition on figurative art).

What a fabulous article. So detailed and well written. Should be in Gourmet Traveller I reckon!

Thanks Justy – I appreciate the feedback all the way from Bordeaux!

Wonderful informative article on Bukhara. The photos are excellent and very evocative.

Thank you – and for inspiring me to go there!

Most interesting and informative. You bring Bukhara back, adding information and perspective. Loved the photos. I can smell those fresh vegetable samosas as they cool in my hand, the steam almost burning when I bite down for a taste.

Thanks Bryan – I’m pleased to hear it brought back such good memories.

Thoroughly enjoyed reading your article! From the phoenixes, mulberry trees, suzani embroidery to the mouth-watering somsas and homemade plov, you have brought back many amazing memories of Bukhara. I might even give the plov from the recipe you provided a go one day soon.

Thanks Wati – pleased you enjoyed it and that it brought back memories of your time in Bukhara.

An interesting article, lovely photos and a great reminder of my time in Uzbekistan in 2016. Whenever I eat mulberries or pomegranates I immediately think of the Silk Road. Yes, one can only tolerate so much lamb!

Thanks Michael, I appreciate your feedback. I’d love to return to Uzbekistan sometime.

Sheridan 🙂