On Becoming A Food Writer

“The words, Rogers! The words!”

The news editor’s voice boomed across the wide open plan office.

He stood up and ambled down the line of desks in the centre of the room, banging loudly on each desk with a rolled-up newspaper.

A couple of the cadets sitting in front of me jumped nervously.

George Williams was a weedy, ginger-haired man of average height with a pale freckled face. He sported a pair of baggy trousers and a pale blue lined shirt.

As soon as I heard my surname, I began to tremble.

Not that he noticed. What I really dreaded was the lack of control I had over my neck which slowly began to flush red.

He continued to slouch towards me.

I quickly rolled another black (carbon paper) into the big, clunky typewriter, pressed firmly on a few keys and put down some words on the pale yellow paper.

“Umberto Soma’s (sic) is one of those rags to riches stories. Not a grandiose one, something more modest than that, but admirable all the same.”

“What’s this?”, he asked as he ripped the paper out of the roller.

“It’s for the Indulgence section of the Weekend Magazine,” I said, the red flush now spreading to my cheeks.

I’d been assigned to airport rounds earlier that week and had already been in trouble for missing a story.

I wasn’t the only one who’d missed it. All the cadets doing airport rounds that day had missed it too.

American singer Frank Sinatra was due in town. But when his jet landed at Sydney Airport from Tokyo, a fleet of limousines suddenly materialised and took his party directly to a hotel in Kings Cross.

For me, it was a lucky escape.

Not long after, provoked by a tabloid story about his well-known mafia connections (and accompanied by photos of some of the famous women in his life) entitled “Sinatra’s Molls”, he dropped a bombshell.

Referring to Australian journalists, he said: “They keep chasing after us. We have to run all day long. They’re parasites who take everything and give nothing. And as for the broads who work for the press, they’re the hookers of the press. I might offer them a buck and a half I’m not sure.”

I’d entered the Fourth Estate with such lofty ideals and had been very excited to get a cadetship on The Australian, one of the classier newspapers at the time, even if owned by Rupert Murdoch.

English was my favourite subject at school and again at University. I wanted to write. I hoped that through becoming a journalist I could change the world.

I rolled another black into the typewriter and kept typing.

The news editor hovered by my side, newspaper in hand.

“A Neapolitan, Umberto arrived in Australia 20 years ago with only a few shillings in his pocket and a 90-litre copper pan in tow. The pan was vital. With it he intended to start making the cheeses for which his family had become renowned in Italy.”

“What is this?” he asked again, banging the newspaper on my desk. “Something to do with cheese?”

He continued to hover and then asked,

“Why would anyone want to write a story about food?”

I tapped out a few more sentences while he stood there looking over my shoulder.

“Ricotta, mascarpone, mozzarella, bocconcini, pecorino and stracchino are his specialties. He works alone, making the cheeses by hand. If you’ve ever wondered how such cheeses are made, Umberto opens his little factory in Marrickville on a Sunday. You’ll have to get there early to beat the hordes of Italian families who roll up carrying bowls, pots and containers to fill with the fresh cheeses. The place reverberates with their voices.”

“Harumph…”, he groaned.

“Well, get on with it,” he added laconically. He began to walk back to his desk, then turned on his heel and returned, this time holding the rolled-up newspaper down by his side.

“One more thing. If you wear those miniskirts to work again, you won’t have a job. The men can’t concentrate.”

He cast a sly glance at my legs and went back to his desk.

It was the early 1970s. Germaine Greer had just published The Female Eunuch and Melbourne singer Helen Reddy had a worldwide hit with I Am Woman which became the theme song for the then rapidly expanding women’s liberation movement.

Almost a decade earlier English supermodel Jean Shrimpton had scandalised the conservative Melbourne establishment at Derby Day by wearing a dress 10cm above the knee.

I was in my early 20s and all my friends were wearing miniskirts.

Any thoughts I’d had that working in a newspaper office would broaden my horizons began to shrink.

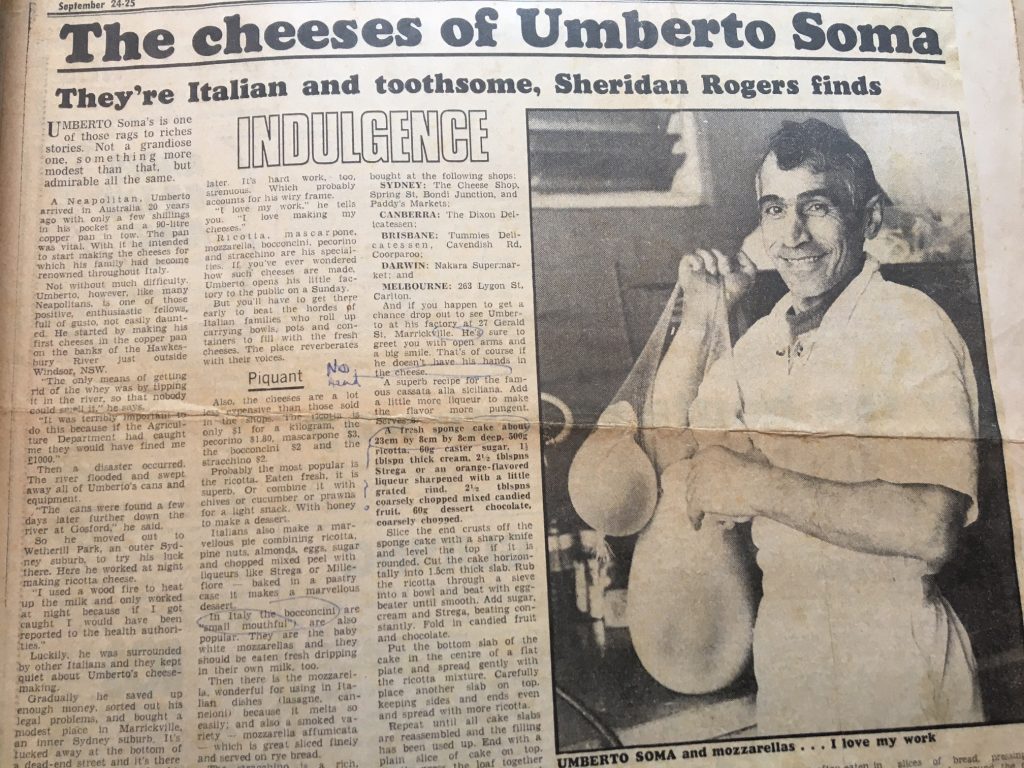

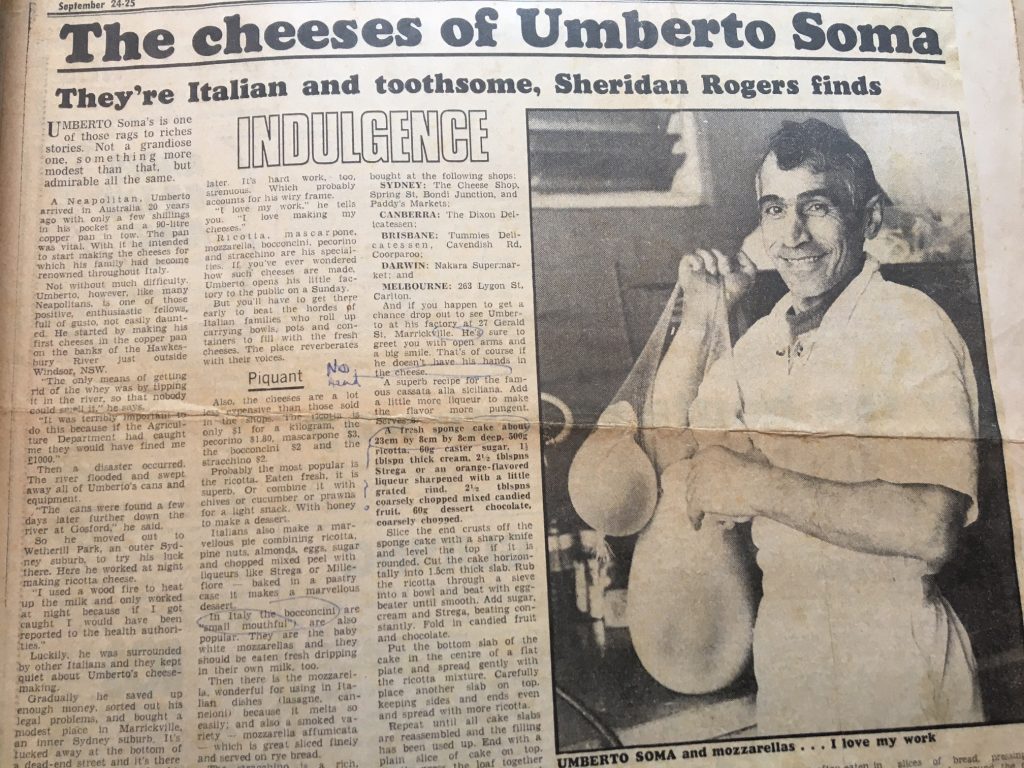

I persisted with the story and a few Saturdays later Robert Drewe, the Arts editor, gave it almost a full page, complete with a photo of Umberto holding a netted stringful of his beloved mozzarella cheeses and smiling broadly. I also included a recipe for Cassata alla Siciliana, though the subs left the heading off it, probably because a recipe in The Australian (i.e. a serious newspaper) was considered trivial.

I was proud of my story. Few Aussies knew anything about fresh Italian cheeses in those days, let alone how they were made, or the story of Umberto, a struggling immigrant from Pimonte, a tiny village south of Naples up in the hills above the Amalfi Coast.

I was still a cadet but my name was on it. A byline in those days was a rare thing.

But my elated feelings didn’t last long.

One evening in the middle of the following week, the editor of the paper, Owen Thomson staggered across the room towards me.

He’d been down at the Evening Star, the local pub otherwise known as the “Evil Star”, a regular hangout for editors and journalists alike.

I’d been rostered onto the late shift and was typing up the shipping news, a tedious job assigned to cadets.

Working late meant I was often sitting at the back of the room on my own, the other cadets – and most of the other journalists – having left earlier.

This left me prey to Mr Thomson’s drunken overtures.

I quickly made sure the top button on my shirt was done up.

“Ah Rogers!,” he cackled. “You think you’re so clever…”

My neck began to turn red.

“Just because you’ve got an Arts Degree doesn’t mean you know how to write for a newspaper…”

He placed a hand on the side of my desk to steady himself then sat sideways on the wooden bar which held the row of desks together.

He leant over me, breathing down my neck.

The heat was spreading to my cheeks.

“And just because your father is on the radio…”, he said, looking at me lasciviously.

But this time it wasn’t fear or intimidation I felt.

I felt like a trapped animal.

The words of Helen Reddy’s hit song came back to me:

“You can bend but never break me

Cause it only serves to make me

More determined to achieve my final goal

And I come back even stronger

Not a novice any longer

‘Cause you’ve deepened the conviction in my soul…”

He began to walk back to his desk, then turned on his heel and returned, this time holding the rolled-up newspaper down by his side.

“One more thing. If you wear those miniskirts to work again, you won’t have a job. The men can’t concentrate.”

He cast a sly glance at my legs and went back to his desk.

It was the early 1970s. Germaine Greer had just published The Female Eunuch and Melbourne singer Helen Reddy had a worldwide hit with I Am Woman which became the theme song for the then rapidly expanding women’s liberation movement.

Almost a decade earlier English supermodel Jean Shrimpton had scandalised the conservative Melbourne establishment at Derby Day by wearing a dress 10cm above the knee.

I was in my early 20s and all my friends were wearing miniskirts.

Any thoughts I’d had that working in a newspaper office would broaden my horizons began to shrink.

I persisted with the story and a few Saturdays later Robert Drewe, the Arts editor, gave it almost a full page, complete with a photo of Umberto holding a netted stringful of his beloved mozzarella cheeses and smiling broadly. I also included a recipe for Cassata alla Siciliana, though the subs left the heading off it, probably because a recipe in The Australian (i.e. a serious newspaper) was considered trivial.

I was proud of my story. Few Aussies knew anything about fresh Italian cheeses in those days, let alone how they were made, or the story of Umberto, a struggling immigrant from Pimonte, a tiny village south of Naples up in the hills above the Amalfi Coast.

I was still a cadet but my name was on it. A byline in those days was a rare thing.

But my elated feelings didn’t last long.

One evening in the middle of the following week, the editor of the paper, Owen Thomson staggered across the room towards me.

He’d been down at the Evening Star, the local pub otherwise known as the “Evil Star”, a regular hangout for editors and journalists alike.

I’d been rostered onto the late shift and was typing up the shipping news, a tedious job assigned to cadets.

Working late meant I was often sitting at the back of the room on my own, the other cadets – and most of the other journalists – having left earlier.

This left me prey to Mr Thomson’s drunken overtures.

I quickly made sure the top button on my shirt was done up.

“Ah Rogers!,” he cackled. “You think you’re so clever…”

My neck began to turn red.

“Just because you’ve got an Arts Degree doesn’t mean you know how to write for a newspaper…”

He placed a hand on the side of my desk to steady himself then sat sideways on the wooden bar which held the row of desks together.

He leant over me, breathing down my neck.

The heat was spreading to my cheeks.

“And just because your father is on the radio…”, he said, looking at me lasciviously.

But this time it wasn’t fear or intimidation I felt.

I felt like a trapped animal.

The words of Helen Reddy’s hit song came back to me:

“You can bend but never break me

Cause it only serves to make me

More determined to achieve my final goal

And I come back even stronger

Not a novice any longer

‘Cause you’ve deepened the conviction in my soul…”

He began to walk back to his desk, then turned on his heel and returned, this time holding the rolled-up newspaper down by his side.

“One more thing. If you wear those miniskirts to work again, you won’t have a job. The men can’t concentrate.”

He cast a sly glance at my legs and went back to his desk.

It was the early 1970s. Germaine Greer had just published The Female Eunuch and Melbourne singer Helen Reddy had a worldwide hit with I Am Woman which became the theme song for the then rapidly expanding women’s liberation movement.

Almost a decade earlier English supermodel Jean Shrimpton had scandalised the conservative Melbourne establishment at Derby Day by wearing a dress 10cm above the knee.

I was in my early 20s and all my friends were wearing miniskirts.

Any thoughts I’d had that working in a newspaper office would broaden my horizons began to shrink.

I persisted with the story and a few Saturdays later Robert Drewe, the Arts editor, gave it almost a full page, complete with a photo of Umberto holding a netted stringful of his beloved mozzarella cheeses and smiling broadly. I also included a recipe for Cassata alla Siciliana, though the subs left the heading off it, probably because a recipe in The Australian (i.e. a serious newspaper) was considered trivial.

I was proud of my story. Few Aussies knew anything about fresh Italian cheeses in those days, let alone how they were made, or the story of Umberto, a struggling immigrant from Pimonte, a tiny village south of Naples up in the hills above the Amalfi Coast.

I was still a cadet but my name was on it. A byline in those days was a rare thing.

But my elated feelings didn’t last long.

One evening in the middle of the following week, the editor of the paper, Owen Thomson staggered across the room towards me.

He’d been down at the Evening Star, the local pub otherwise known as the “Evil Star”, a regular hangout for editors and journalists alike.

I’d been rostered onto the late shift and was typing up the shipping news, a tedious job assigned to cadets.

Working late meant I was often sitting at the back of the room on my own, the other cadets – and most of the other journalists – having left earlier.

This left me prey to Mr Thomson’s drunken overtures.

I quickly made sure the top button on my shirt was done up.

“Ah Rogers!,” he cackled. “You think you’re so clever…”

My neck began to turn red.

“Just because you’ve got an Arts Degree doesn’t mean you know how to write for a newspaper…”

He placed a hand on the side of my desk to steady himself then sat sideways on the wooden bar which held the row of desks together.

He leant over me, breathing down my neck.

The heat was spreading to my cheeks.

“And just because your father is on the radio…”, he said, looking at me lasciviously.

But this time it wasn’t fear or intimidation I felt.

I felt like a trapped animal.

The words of Helen Reddy’s hit song came back to me:

“You can bend but never break me

Cause it only serves to make me

More determined to achieve my final goal

And I come back even stronger

Not a novice any longer

‘Cause you’ve deepened the conviction in my soul…”

He began to walk back to his desk, then turned on his heel and returned, this time holding the rolled-up newspaper down by his side.

“One more thing. If you wear those miniskirts to work again, you won’t have a job. The men can’t concentrate.”

He cast a sly glance at my legs and went back to his desk.

It was the early 1970s. Germaine Greer had just published The Female Eunuch and Melbourne singer Helen Reddy had a worldwide hit with I Am Woman which became the theme song for the then rapidly expanding women’s liberation movement.

Almost a decade earlier English supermodel Jean Shrimpton had scandalised the conservative Melbourne establishment at Derby Day by wearing a dress 10cm above the knee.

I was in my early 20s and all my friends were wearing miniskirts.

Any thoughts I’d had that working in a newspaper office would broaden my horizons began to shrink.

I persisted with the story and a few Saturdays later Robert Drewe, the Arts editor, gave it almost a full page, complete with a photo of Umberto holding a netted stringful of his beloved mozzarella cheeses and smiling broadly. I also included a recipe for Cassata alla Siciliana, though the subs left the heading off it, probably because a recipe in The Australian (i.e. a serious newspaper) was considered trivial.

I was proud of my story. Few Aussies knew anything about fresh Italian cheeses in those days, let alone how they were made, or the story of Umberto, a struggling immigrant from Pimonte, a tiny village south of Naples up in the hills above the Amalfi Coast.

I was still a cadet but my name was on it. A byline in those days was a rare thing.

But my elated feelings didn’t last long.

One evening in the middle of the following week, the editor of the paper, Owen Thomson staggered across the room towards me.

He’d been down at the Evening Star, the local pub otherwise known as the “Evil Star”, a regular hangout for editors and journalists alike.

I’d been rostered onto the late shift and was typing up the shipping news, a tedious job assigned to cadets.

Working late meant I was often sitting at the back of the room on my own, the other cadets – and most of the other journalists – having left earlier.

This left me prey to Mr Thomson’s drunken overtures.

I quickly made sure the top button on my shirt was done up.

“Ah Rogers!,” he cackled. “You think you’re so clever…”

My neck began to turn red.

“Just because you’ve got an Arts Degree doesn’t mean you know how to write for a newspaper…”

He placed a hand on the side of my desk to steady himself then sat sideways on the wooden bar which held the row of desks together.

He leant over me, breathing down my neck.

The heat was spreading to my cheeks.

“And just because your father is on the radio…”, he said, looking at me lasciviously.

But this time it wasn’t fear or intimidation I felt.

I felt like a trapped animal.

The words of Helen Reddy’s hit song came back to me:

“You can bend but never break me

Cause it only serves to make me

More determined to achieve my final goal

And I come back even stronger

Not a novice any longer

‘Cause you’ve deepened the conviction in my soul…”

Oh, no! You can’t stop there? Fascinating! Are you writing your autobiography?

Thanks, Mercedes…not yet, but maybe this year 😉

Well, I’ll be looking forward to it and will be one of the first to buy your book!

Thank you for your enthusiastic support, Mercedes – it might take a while! 🙂