When Fiorenzo Giolito’s grandmother, Mariet Almonte, first started selling local cheese in the 1920s she would transport them 60 Km from Bra by horse to Turin.

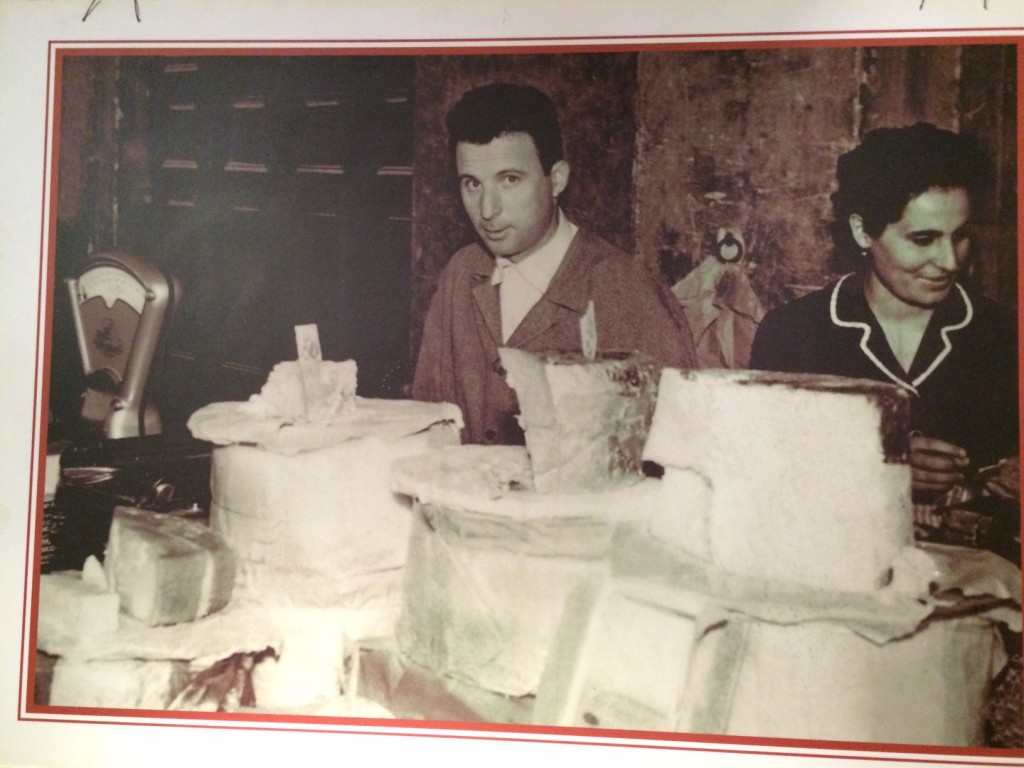

It was she who introduced the Genovese to Bra Duro, a hard cheese which travels well and doesn’t require much looking after – and it was the Genovese who took the cheese with them on ships when they emigrated from Genoa to America. After World War II, her son Francesco together with his wife Emma, took over the business and began selling cheeses at the weekly farmers markets throughout the Piedmontese province of Cuneo.

Today, grandson Fiorenzo sells cheeses wholesale to the famous Italian food emporium Eataly (which originated in Turin) choosing products and helping producers get their cheeses on Eataly’s shelves in Italy, Tokyo, New York (and soon to be in Sao Paolo, Munich – and one day hopefully, Sydney) . He’s also one of the cofounders of Cheese, Slow Food’s biennial festival which will be held in Bra this year.

If you’re lucky enough to find him behind the counter at Giolito Formaggi, his cheese distribution outlet in the centre of Bra, you’ll be in for some fun.

A small group of us had booked a cheese-tasting with his informative assistant Luca Coco, but it didn’t take long before Fiorenzo had joined in and was wielding a cheese knife, punching mozzarella balls,– and once the tour was over, encouraging us to match numerous local wines with various cheeses.

“Life’s too short not to eat and drink well,” he told us, with a sparkle in his eye. “I took up the business almost by accident and cheese became my passion.”

Cheeses on display at Giolito

Before the actual tasting, Luca took us on a tour, showing us where various cheeses are cut and packaged, the refrigerated areas where they are stored, and the cellar downstairs where the wheels of parmigiano reggiano are kept and also where Fiorenzo has set up a small museum. Here you can see various tools and objects collected throughout the valleys of Cuneo in Piemonte which are used for making cheese and get an idea of the step-by-step process of artisan cheesemakers.

“We work mainly with wholesalers,” he told us, “and we ship our cheeses all over the world. Our job is to have a large variety of cheeses such as pecorino from Tuscany and parmigiano reggiano on hand so that people can buy a wide range from us, including half wheels.

Fiorenzo deals with 20 – 25 local producers who follow the ancient Italian custom of transumanza (“crossing the land”), a twice yearly migration of sheep and cows from the highlands to the lowlands, and vice versa. They follow the grasses up and down the Alps which means that in summer, their milk is perfumed with fresh flowers and grasses.

“Their cheeses must be aged in the area of production and we then store them here,” he said

He often visits producers on his motorbike on Sundays and is always on the look-out for something new.

“Most robiolas (a soft-ripened cheese of the stracchino family) are made with mixed milk, but we now have a robiola di roccaverano, made from 100% goat’s milk – the only Italian goat cheese to have the Dop (Denominazione di Origine Protetta) accreditation.”

I was especially keen to see the legendary castelmagno cheese, a Dop semi-hard, semi-fat blue cheese made not far from Bra in Castelmagno, Pradleves and Monterosso Grana from cow’s milk with a small addition of a mixture of sheep and/or goat’s milk.

It’s an ancient cheese with origins dating back to 1277 (around about the same time as the origin of gorgonzola). “We use castelmagno a lot in the kitchen,” said Luca. “I prefer to use it in cooking with gnocchi and risotto.”

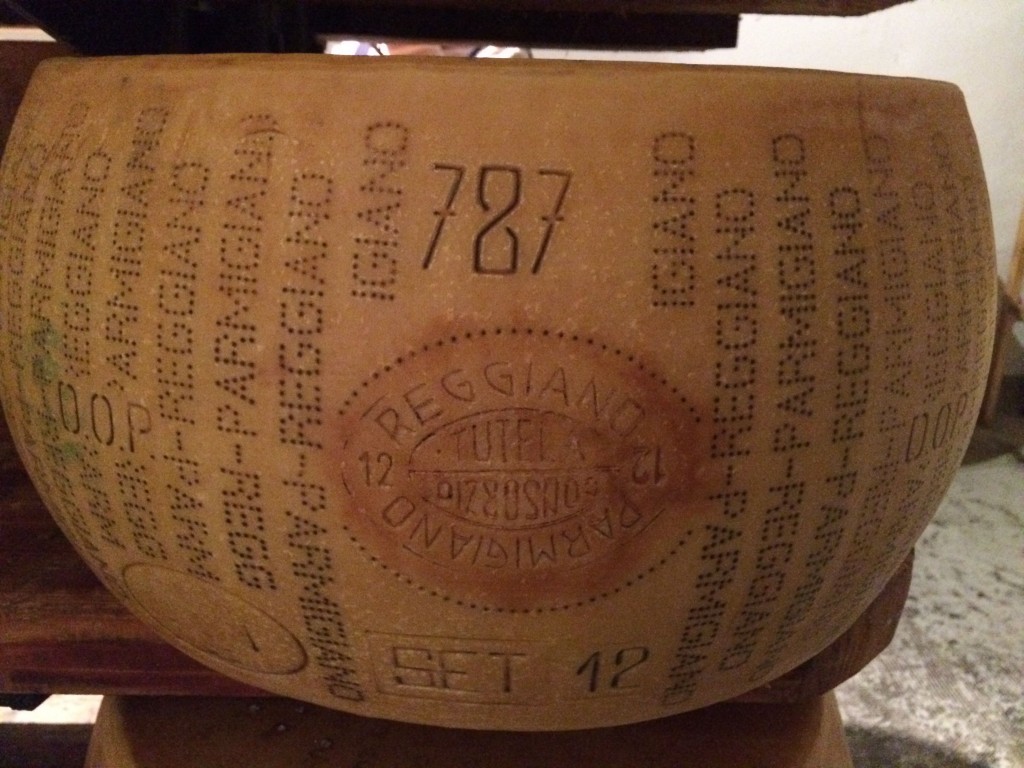

One of the many interesting things I learnt on the tour with Luca was that parmigiano reggiano is produced south of the Po River (i.e. in Parma, Bologna, Reggio Emilia and Modena) and that grana padana is produced north of the Po.

Six hundred litres of milk is required to make one wheel of cheese and an average wheel weighs 38Kg – 40Kg. Parmigiano must be stamped with a number signifying the producer, plus month and year of production and the milk for this king of cheeses must come from cows who have grazed only on grass and hay whereas for grana padana, cows can be fed corn and silage.

“Bibbiano near Reggio Emilia is the best area for parmigiano because it is mountainous,” said Luca. “Once it has been aged, it must be checked to ensure it’s perfect and that there are no holes.”

After we’d all tapped the cheese with a small mallet to ensure it had a perfect sound, it was back upstairs to the tasting room where we sat around a long wooden table.

Cheese Tasting Room Giolito’s (the warm fire is welcome after visiting the refrigerated cheese rooms)

We tasted nine cheeses, starting with one invented by Fiorenzo, the. G. da manicocomio (which means “madhouse” I dialect), a seductive creamy mixture of mascarpone, gorgonzola (and Fiorenzo’s secret ingredient). Divine!

It was followed by two rascheras: di pianura – where the cows stay in the same place all year; and di alpeggio – where the cows move up and down the Alps; a braciuk, another cheese invented by Fiorenzo meaning “drunken Bra,” in which young Bra Tenero wheels are aged for an additional three months in barrels of leftover grape must from surrounding vineyards, resulting in a slightly boozy cheese.

Then came a formagetta di capra abate (refined and elegant, made with 100% goat’s milk) followed by a toma di piemontese, which I found rather soapy; a magnificent castagno (made from a mix of cow and goats milk) which was , for me, the highlight of the tasting; a castelmagno and a delicious stilton dressed with port.

Halfway through the tasting Fiorenzo lit the fire, pulled out another bottle of wine and began to regale us with stories. And I seem to remember he even asked if we’d ever played “strip-cheese”. Cheeky (or should that be “cheesy”?)