The Oldest Foods On Earth

Imagine this:

There’s a knock on your front door. You open it. There’s a stranger there, pleasant enough, say’s he’s looking around the neighbourhood for somewhere to live.

You invite him in, give him a cup of tea. He goes on his way.

Some time later, he appears at the door again. This time with several friends, some of whom you really don’t like the look of. Somewhat reticently, you invite them in. Gradually, they begin to take over your house. Where you thought they only wanted to look around, it becomes obvious they’re not going away.

They bring in their own food, spread themselves around all the rooms, trash your furniture, clog up your plumbing and generally wreck your house while hardly taking notice of you.

You and your family try and kick them out, but they’re too many and too strong. And they have weapons.

Eventually you find yourself sleeping in the backyard, eating their leftovers. They’ve taken over completely.

This was the scene depicted by John Newton, author of The Oldest Foods On Earth: A History of Australian Native Foods, at a lecture on Australian native foods at Sydney University this week.

Newton had been invited by the Veterinary Sciences Department to participate in a series of seminars being conducted on indigenous foods.

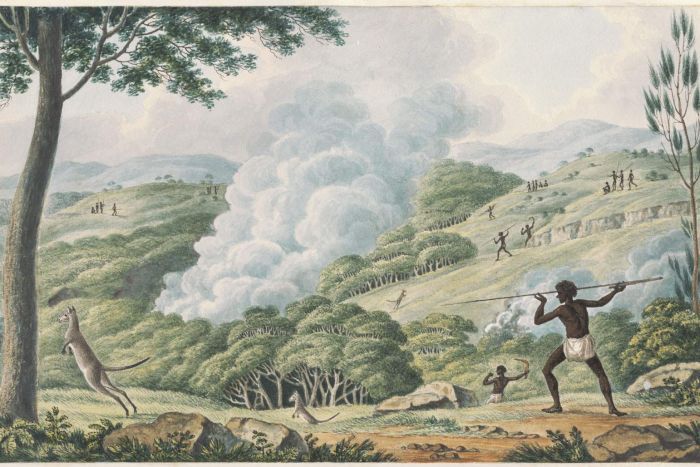

Over the past 20 years, a seismic shift in the writing of the history of Indigenous Australia has taken place. Historian Henry Reynolds has shone a light on the high level of violence and conflict involved in the colonisation of Australia.

Bill Gammage’s remarkable book The Biggest Estate on Earth: how Aborigines made Australia exploded the myth that pre-settlement Australia was an untamed wilderness and revealed the complex, country-wide systems of land management used by Aboriginal people pre-1788 while Bruce Pascoe challenged the claim that pre-colonial Aboriginal society was essentially a hunter-gatherer society in Dark Emu.

Last year Newton published his book, one which celebrates Australia’s unique flora and fauna and questions why we continue to favour superfoods from exotic locations, yet shun the foods which nourished Aboriginal people for over 50,000 years.

“We say we revere sustainable local produce, yet ignore Australian native plants and animals that are better for the land than European ones.”

The scene he painted in the first few minutes of his talk this week was so vivid that it haunted me for hours afterwards.

So what were the most dangerous and destructive things brought to Australia by those strangers?

“To my way of thinking it was the livestock, the food plants and the system of agriculture they imported from the northern hemisphere,” he told us.

Until very recently. we knew nothing about indigenous agriculture.

“We didn’t know the indigenous population of the land we now call Australia reared possums, emus, dingos, and cassowaries; penned young pelican chicks and let parent birds fatten them. Carried fish and crayfish stock across country. That there were duck nets on the rivers with sinkers and floaters; fishing nets of European quality, with the mesh and knot varied to suit their prey placed in the right waters.”

The sheep, cattle, goats and pigs brought here by the British ruined the delicate topsoil, while introduced European seeds were alien to the land and to the indigenous people.

Food racism, he calls it: you’ll need to read his powerful book to explore the length and depth of his argument.

For me, as an ambassador for Outback Spirit Foundation’s bush tomato project, I was most interested in his views on how we can get these highly nutritious foods not just into our trendy restaurants but into the Australian home kitchen and diet, and how we can work with the original custodians of the land to develop them.

“We can’t just do as we have done, and are to a great extent still doing: take over,” he told us. “We have to learn in all aspects of the relationship to walk together. We have lost 230 years of cultivation of these foods. Europeans arrived on this island continent in 1788, and for the next 230 years, virtually ignored the foods that had sustained the original inhabitants for over 50,000 years. That much we know. But what are the consequences of this?

To answer that question, Newton talked about the tomato, which originated in Peru.

The commonest, Lycopersicon esculentum, is one of nine varieties of wild tomatoes still growing there. It was imported to Europe in the first half of the 15th century and first appeared in Seville in the early 16th century after which it travelled to Italy, where it was treated with suspicion. The first recipe using the tomato didn’t appear, in an Italian cookbook until 1692 in a recipe called ‘Tomato sauce, Spanish style’ From the 17th century on, it has been cultivated and developed so that we now have a wide variety of tomatoes available in the 21st century.

“That’s 400 years of cultivation. We’ve been here on this continent for a little over 200 years, and have only been cultivating and attempting to develop Australian natives for twenty years.”

The scene he painted in the first few minutes of his talk this week was so vivid that it haunted me for hours afterwards.

So what were the most dangerous and destructive things brought to Australia by those strangers?

“To my way of thinking it was the livestock, the food plants and the system of agriculture they imported from the northern hemisphere,” he told us.

Until very recently. we knew nothing about indigenous agriculture.

“We didn’t know the indigenous population of the land we now call Australia reared possums, emus, dingos, and cassowaries; penned young pelican chicks and let parent birds fatten them. Carried fish and crayfish stock across country. That there were duck nets on the rivers with sinkers and floaters; fishing nets of European quality, with the mesh and knot varied to suit their prey placed in the right waters.”

The sheep, cattle, goats and pigs brought here by the British ruined the delicate topsoil, while introduced European seeds were alien to the land and to the indigenous people.

Food racism, he calls it: you’ll need to read his powerful book to explore the length and depth of his argument.

For me, as an ambassador for Outback Spirit Foundation’s bush tomato project, I was most interested in his views on how we can get these highly nutritious foods not just into our trendy restaurants but into the Australian home kitchen and diet, and how we can work with the original custodians of the land to develop them.

“We can’t just do as we have done, and are to a great extent still doing: take over,” he told us. “We have to learn in all aspects of the relationship to walk together. We have lost 230 years of cultivation of these foods. Europeans arrived on this island continent in 1788, and for the next 230 years, virtually ignored the foods that had sustained the original inhabitants for over 50,000 years. That much we know. But what are the consequences of this?

To answer that question, Newton talked about the tomato, which originated in Peru.

The commonest, Lycopersicon esculentum, is one of nine varieties of wild tomatoes still growing there. It was imported to Europe in the first half of the 15th century and first appeared in Seville in the early 16th century after which it travelled to Italy, where it was treated with suspicion. The first recipe using the tomato didn’t appear, in an Italian cookbook until 1692 in a recipe called ‘Tomato sauce, Spanish style’ From the 17th century on, it has been cultivated and developed so that we now have a wide variety of tomatoes available in the 21st century.

“That’s 400 years of cultivation. We’ve been here on this continent for a little over 200 years, and have only been cultivating and attempting to develop Australian natives for twenty years.”

We have a long way to go. But a start has been made. Gardens have been started all around the country and in remote areas to provide food, employment and income for Indigenous people.

Much more needs to be done. Juleigh and Ian Robins, the entrepreneurial couple behind Outback Spirit’s range of native sauces and preserves (which are available in Coles nationally) set up the Outback Spirit Foundation in 2008 to assist Aboriginal farmers to establish native food plantations and orchards on their land.

The target is to raise $60K so that the Indigenous owned and managed farm will expand to Stage 2 and farmers will set up two adjacent farms for a related Aboriginal family group to grow bush tomatoes commercially (they have already raised $40K towards the project from two leadership donors).

Donations will also enable the Foundation to fund the horticultural bacteriologist and plant physiologist, Max Emery from Desert Garden Produce, to assist more Aboriginal farmers living in Central Australia to set up their own enterprises to grow and supply bush tomatoes commercially.

Check out this video and please try to support the campaign here.

Every dollar you donate will be quadrupled.

We have a long way to go. But a start has been made. Gardens have been started all around the country and in remote areas to provide food, employment and income for Indigenous people.

Much more needs to be done. Juleigh and Ian Robins, the entrepreneurial couple behind Outback Spirit’s range of native sauces and preserves (which are available in Coles nationally) set up the Outback Spirit Foundation in 2008 to assist Aboriginal farmers to establish native food plantations and orchards on their land.

The target is to raise $60K so that the Indigenous owned and managed farm will expand to Stage 2 and farmers will set up two adjacent farms for a related Aboriginal family group to grow bush tomatoes commercially (they have already raised $40K towards the project from two leadership donors).

Donations will also enable the Foundation to fund the horticultural bacteriologist and plant physiologist, Max Emery from Desert Garden Produce, to assist more Aboriginal farmers living in Central Australia to set up their own enterprises to grow and supply bush tomatoes commercially.

Check out this video and please try to support the campaign here.

Every dollar you donate will be quadrupled.

The scene he painted in the first few minutes of his talk this week was so vivid that it haunted me for hours afterwards.

So what were the most dangerous and destructive things brought to Australia by those strangers?

“To my way of thinking it was the livestock, the food plants and the system of agriculture they imported from the northern hemisphere,” he told us.

Until very recently. we knew nothing about indigenous agriculture.

“We didn’t know the indigenous population of the land we now call Australia reared possums, emus, dingos, and cassowaries; penned young pelican chicks and let parent birds fatten them. Carried fish and crayfish stock across country. That there were duck nets on the rivers with sinkers and floaters; fishing nets of European quality, with the mesh and knot varied to suit their prey placed in the right waters.”

The sheep, cattle, goats and pigs brought here by the British ruined the delicate topsoil, while introduced European seeds were alien to the land and to the indigenous people.

Food racism, he calls it: you’ll need to read his powerful book to explore the length and depth of his argument.

For me, as an ambassador for Outback Spirit Foundation’s bush tomato project, I was most interested in his views on how we can get these highly nutritious foods not just into our trendy restaurants but into the Australian home kitchen and diet, and how we can work with the original custodians of the land to develop them.

“We can’t just do as we have done, and are to a great extent still doing: take over,” he told us. “We have to learn in all aspects of the relationship to walk together. We have lost 230 years of cultivation of these foods. Europeans arrived on this island continent in 1788, and for the next 230 years, virtually ignored the foods that had sustained the original inhabitants for over 50,000 years. That much we know. But what are the consequences of this?

To answer that question, Newton talked about the tomato, which originated in Peru.

The commonest, Lycopersicon esculentum, is one of nine varieties of wild tomatoes still growing there. It was imported to Europe in the first half of the 15th century and first appeared in Seville in the early 16th century after which it travelled to Italy, where it was treated with suspicion. The first recipe using the tomato didn’t appear, in an Italian cookbook until 1692 in a recipe called ‘Tomato sauce, Spanish style’ From the 17th century on, it has been cultivated and developed so that we now have a wide variety of tomatoes available in the 21st century.

“That’s 400 years of cultivation. We’ve been here on this continent for a little over 200 years, and have only been cultivating and attempting to develop Australian natives for twenty years.”

The scene he painted in the first few minutes of his talk this week was so vivid that it haunted me for hours afterwards.

So what were the most dangerous and destructive things brought to Australia by those strangers?

“To my way of thinking it was the livestock, the food plants and the system of agriculture they imported from the northern hemisphere,” he told us.

Until very recently. we knew nothing about indigenous agriculture.

“We didn’t know the indigenous population of the land we now call Australia reared possums, emus, dingos, and cassowaries; penned young pelican chicks and let parent birds fatten them. Carried fish and crayfish stock across country. That there were duck nets on the rivers with sinkers and floaters; fishing nets of European quality, with the mesh and knot varied to suit their prey placed in the right waters.”

The sheep, cattle, goats and pigs brought here by the British ruined the delicate topsoil, while introduced European seeds were alien to the land and to the indigenous people.

Food racism, he calls it: you’ll need to read his powerful book to explore the length and depth of his argument.

For me, as an ambassador for Outback Spirit Foundation’s bush tomato project, I was most interested in his views on how we can get these highly nutritious foods not just into our trendy restaurants but into the Australian home kitchen and diet, and how we can work with the original custodians of the land to develop them.

“We can’t just do as we have done, and are to a great extent still doing: take over,” he told us. “We have to learn in all aspects of the relationship to walk together. We have lost 230 years of cultivation of these foods. Europeans arrived on this island continent in 1788, and for the next 230 years, virtually ignored the foods that had sustained the original inhabitants for over 50,000 years. That much we know. But what are the consequences of this?

To answer that question, Newton talked about the tomato, which originated in Peru.

The commonest, Lycopersicon esculentum, is one of nine varieties of wild tomatoes still growing there. It was imported to Europe in the first half of the 15th century and first appeared in Seville in the early 16th century after which it travelled to Italy, where it was treated with suspicion. The first recipe using the tomato didn’t appear, in an Italian cookbook until 1692 in a recipe called ‘Tomato sauce, Spanish style’ From the 17th century on, it has been cultivated and developed so that we now have a wide variety of tomatoes available in the 21st century.

“That’s 400 years of cultivation. We’ve been here on this continent for a little over 200 years, and have only been cultivating and attempting to develop Australian natives for twenty years.”

Juleigh Robins with Outback Spirit Supply Chain partners Ruth and Max Emery, Rainbow Valley, Northern Territory with the bush tomato crop.