Hungry in the City

Bill Lemon is standing next to a bunsen burner at the top of Martin Place in Sydney’s CBD stirring a large pot of vegetable soup.

It’s a healthy, colourful mix of carrots, celery, silver beet, broccoli, onions and sweet potatoes.

“No salt,” says Bill. “I haven’t added any salt.”

Now retired, Bill is a former chef and volunteer for a homeless charity.

These days he helps out regularly at the homeless shelter opposite the Reserve Bank and across from Sydney Hospital in what’s considered the swanky part of town.

The kitchen is open 24 hours a day and is a magnet for the city’s homeless, many of whom come from far away to eat here.

Run by (the late) Lanz Priestley, a prominent figure in the local Occupy movement, the “24/7 Street Kitchen Safe Space” has been up and running now for six months.

It straddles a long strip of Martin Place between Macquarie Street and Phillip Street and is sheltered by scaffolding from the neighbouring construction site. A tall crane swings over the top.

“The building site has put up notices to move us on,” says Priestley. “The Council asked them to do it because they’re reluctant to initiate anything themselves.

“The Homelessness Unit at the Council tried for the fourth time to remove the kitchen on March 8th, but they haven’t tried since because of widespread public protest.

“Our first priority is to offer a safe place. The kitchen is our second priority. Seventy people are sleeping here at present. They feel safe here.”

Priestley refuses to engage with the property industry.

“Places like Matthew Talbot charge $26 a night. For people on the dole, that’s 80% of their income. We call it ‘the gaol you pay for’.

“It’s the same with the Salvos and Mission Australia – they’re there to grow their business, not help the disadvantaged,” says Priestley.

The day I’m there, one of the men is huddled up on his makeshift bed reading Bill Bryson’s Down Under. A grey-bearded middle aged man called Otto tells me he’s come for some food. He’s homeless but his camp is on the other side of the city.

One of the tables is covered in loaves of donated bread.

Bill tells me that bread is delivered daily and that the kitchen gets through 75 litres of milk a day. Someone has just dropped off some hot & spicy SPAM.

“Rosie’s going down to Coles later to buy steaks for tonight,” he says.

“Don’t know what we’d do without Rosie.”

I try to chat to her but she’s preoccupied scrubbing a large pot and wiping down surfaces with a soapy rag.

The vegetable soup, basket of fruit, milk and steaks on offer the day I visited help explain why the 24/7 Kitchen has become so popular.

Recent research from the City of Sydney found that a staggering 8% of residents (or 17,000 people in the L.G.A.) were food insecure, struggling with the challenge of putting good, healthy, and sustainable food on the table.

For the homeless and those with low income, healthy foods are too expensive so they opt for a cheap fast food option once a day as their only source of food (“bad food is cheaper than good food”); 43% of households choose cheap carbs over fruit and veg; many don’t have a fridge to store food; and low income people prioritise rent and bills over food.

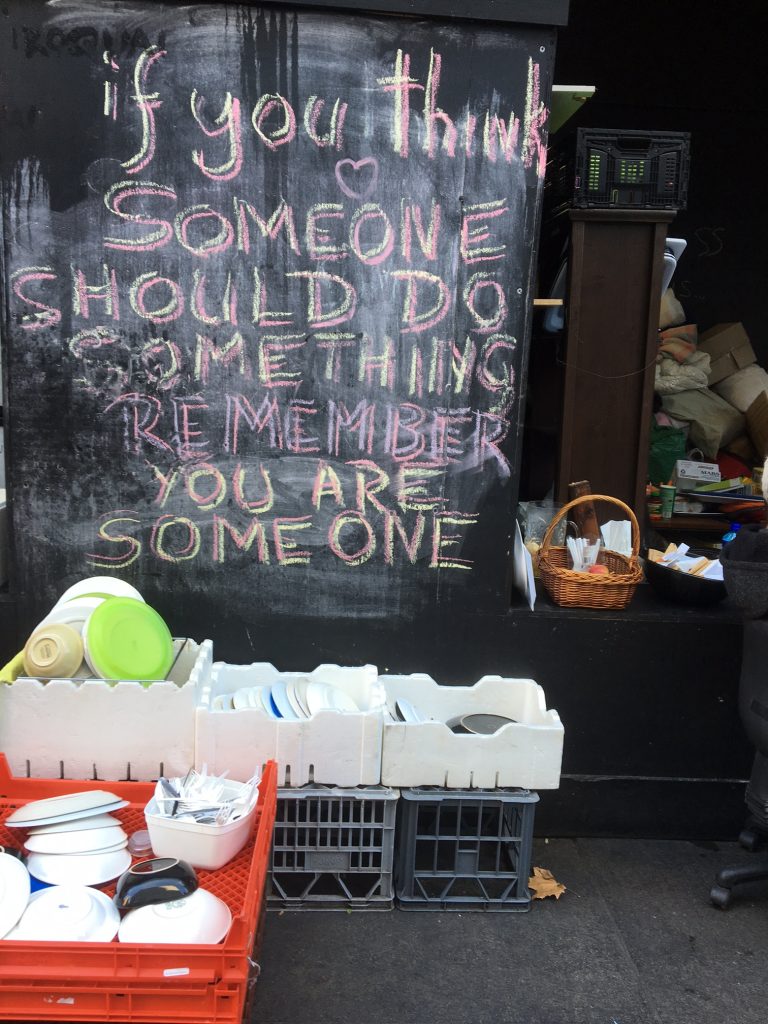

At the Eating in the City seminar held by the Sydney Environment Institute (S.E.I.) at Sydney University this week, questions were asked about what is being done—and what more can be done—to help address this problem and what food-related urban planning policy actions are required to promote food justice.

Up to half a million Aussies visit a food bank once a month.

“That’s unconscionable, unjust and unsustainable,” Professor David Schlosberg, co-director of S.E.I. told the audience.

Food insecurity, he said, is about more than food and encompasses other issues such as housing affordability, efficient public transport and broader physical food spaces (such as community gardens, commercial kitchen spaces and larger scale vertical farming).

“We have an enlightened ideal that we’re moving towards more justice, but we’re not.”

Since 1982, 22 per cent of all growth in Australia’s household income went to the richest 1 per cent, an era which has been designated The Great Divergence.

Just a block down Maritn Place is the ritzy Commonwealth Bank where the rich can feel “safe as the bank”

“Urban renewal is transforming our city and relative inequality is rising,” Alison Heller, Manager of Social Strategy at City of Sydney, told us.

“People skip meals. Over 24% of residents couldn’t raise $2000 in two days in an emergency.

“Food insecurity is a critical public policy issue in a country where there’s plenty of food, yet many are unaware of this problem in out midst.”

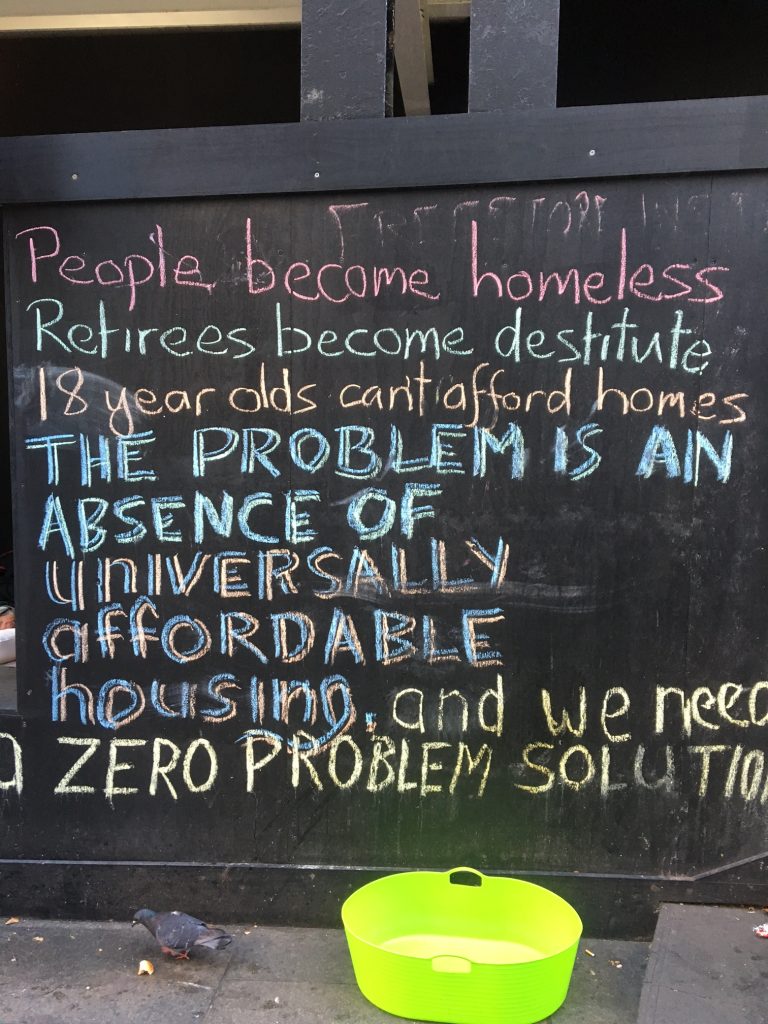

As Ann Deslandes, a writer and social researcher at Sydney University, has pointed out:

“Sydney’s 24/7 Street Kitchen and Safe Space should be able to exist without municipal, police or public harassment, because as long as we can’t solve the problem of homelessness…the least we can do is ensure our public spaces make it possible for people to feel somewhat at home on their own terms.”

Schlosberg says he’s looking forward to working with the City of Sydney on a new urban food system.

“Sydney can become an example of best practice. There’s a lot of potential here.”

But how much longer will Sydney’s homeless men and women have to wait?

Sydney’s 24-7 Street Kitchen and Safe Space has an ongoing call-out for donations. They can be contacted on 0410 722 000 or through their Facebook page. And members of the public are welcome to drop off donations at the site directly.

Hi sheridan.

It’s a great story and a great ending. Good photos too!

Justy

Thanks Justy