Kong Hee Fatt Choy!

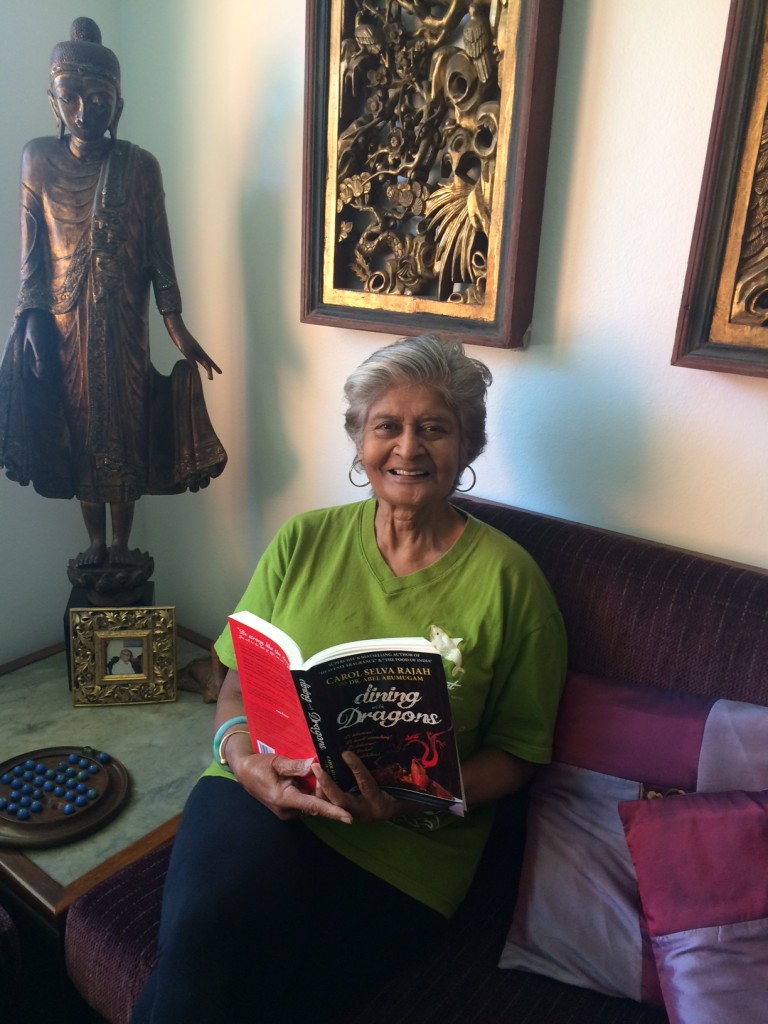

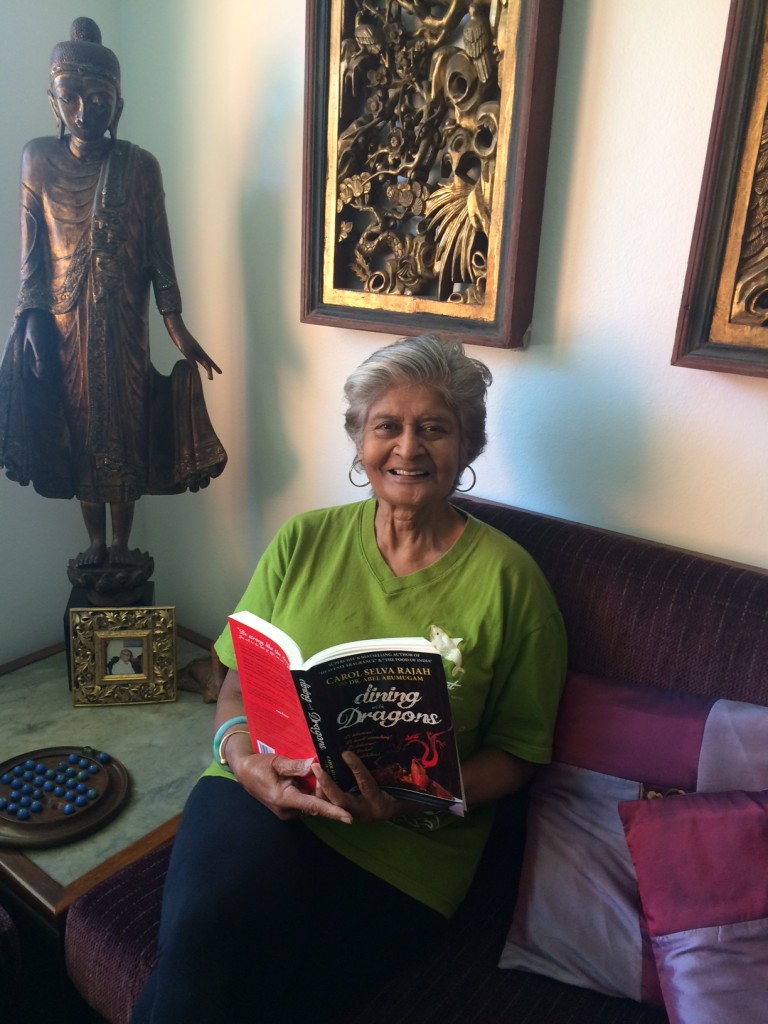

I was running late for my appointment with Carol SelvaRajah, one of Australia’s leading exponents of Nonya and Malaysian cooking. When I arrived, she was on the phone to her brother in Kuala Lumpur, Dr Abel Arumugam.

She opened the front door, waving me in, while continuing with the instructions for chicken rendang.

“After you’ve marinated the chicken in the paste, fry it until coloured on both sides, then add the coconut milk.”

“Stand there and stir it. Be very careful not to let it boil or catch on the bottom.”

She repeated both instructions, speaking clearly and firmly.

Rendang is a rich, spicy dish of 17 herbs and spices with dry roasted coconut and a dark soy sauce, typical of many of the dishes she cooks and has written recipes for. Traditionally it is made with tough old buffalo meat, simmered for eight hours and served for special occasions such as village festivals and weddings. The chicken rendang her brother was making is a simplified version.

I’d come to talk to Carol about her memoir, Dining with Dragons, which she co-authored with her brother.  Unlike her previous 14 cookbooks, this one is a memoir spanning three generations of family life in Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Canada, the US and Australia.

Food, and her memories associated with the smelling, eating and cooking of it from early childhood through to the present, is a major theme, as is learning from the past.

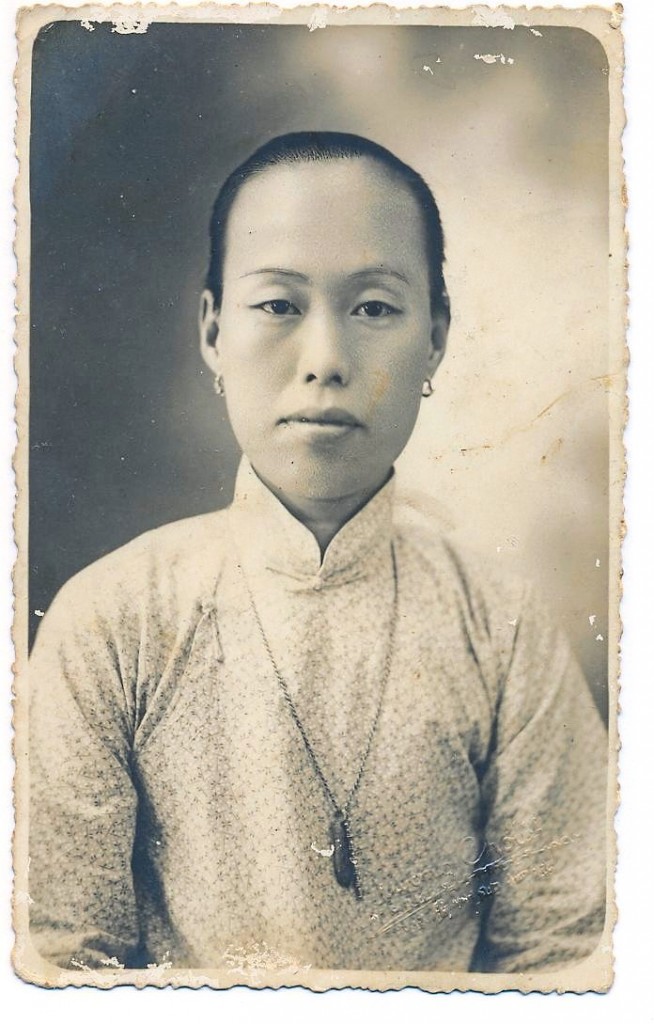

The book opens with a vivid image of 22-year old Kim bent over a hoong lo (earthen stove) near a bridge construction site on the Pearl River, Canton, in 1924. Kim’s husband Chun is one of the bridge-builders and they have a 5 year old boy and 3 year old daughter with another on the way.

“Kim squatted close to the steaming pot and, with long handled chopsticks, drew out a few grains of rice from the chuk (rice congee) she was cooking. She tested the grains, then dragged a wooden bucket closer, scraped the bottom of the pot, and dropped in a handful of chopped vegetables and some damp rock salt. A few drops of soy sauce or precious sesame oil, added just before eating, would finish it. There were no more dried prawns and rendered pork, but the bridge was nearing completion and Chun would be paid. In the meantime, plain congee would have to do.”

Chun never returned from work that day. Part of the bridge collapsed, killing him as it fell.

Having married Chun, Kim now belonged to his family and was considered as nothing but chattel. Her mother-in-law treated her cruelly, blaming Kim for Chun’s death while her bothers-in-law made it clear she would be used as a concubine once her third child was born. Like many Chinese women at that time, Kim risked being condemned to oppression for life because of her gender.

But Kim remembered something her mother had told her, something whispered into her tiny ear to guide her through life in the lucky year of the dragon.

“Be strong like the dragon. You will be the salt of life, nui tsai – girl child.”

Unlike her previous 14 cookbooks, this one is a memoir spanning three generations of family life in Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Canada, the US and Australia.

Food, and her memories associated with the smelling, eating and cooking of it from early childhood through to the present, is a major theme, as is learning from the past.

The book opens with a vivid image of 22-year old Kim bent over a hoong lo (earthen stove) near a bridge construction site on the Pearl River, Canton, in 1924. Kim’s husband Chun is one of the bridge-builders and they have a 5 year old boy and 3 year old daughter with another on the way.

“Kim squatted close to the steaming pot and, with long handled chopsticks, drew out a few grains of rice from the chuk (rice congee) she was cooking. She tested the grains, then dragged a wooden bucket closer, scraped the bottom of the pot, and dropped in a handful of chopped vegetables and some damp rock salt. A few drops of soy sauce or precious sesame oil, added just before eating, would finish it. There were no more dried prawns and rendered pork, but the bridge was nearing completion and Chun would be paid. In the meantime, plain congee would have to do.”

Chun never returned from work that day. Part of the bridge collapsed, killing him as it fell.

Having married Chun, Kim now belonged to his family and was considered as nothing but chattel. Her mother-in-law treated her cruelly, blaming Kim for Chun’s death while her bothers-in-law made it clear she would be used as a concubine once her third child was born. Like many Chinese women at that time, Kim risked being condemned to oppression for life because of her gender.

But Kim remembered something her mother had told her, something whispered into her tiny ear to guide her through life in the lucky year of the dragon.

“Be strong like the dragon. You will be the salt of life, nui tsai – girl child.” Kim’s brothers had already left China to find work in Sin-Ka-Por (Singapore) and their departure encouraged her to plan her own. Leaving the three children with her mother, she fled to Hong Kong and then to Singapore where she soon found work as an amah (nanny).

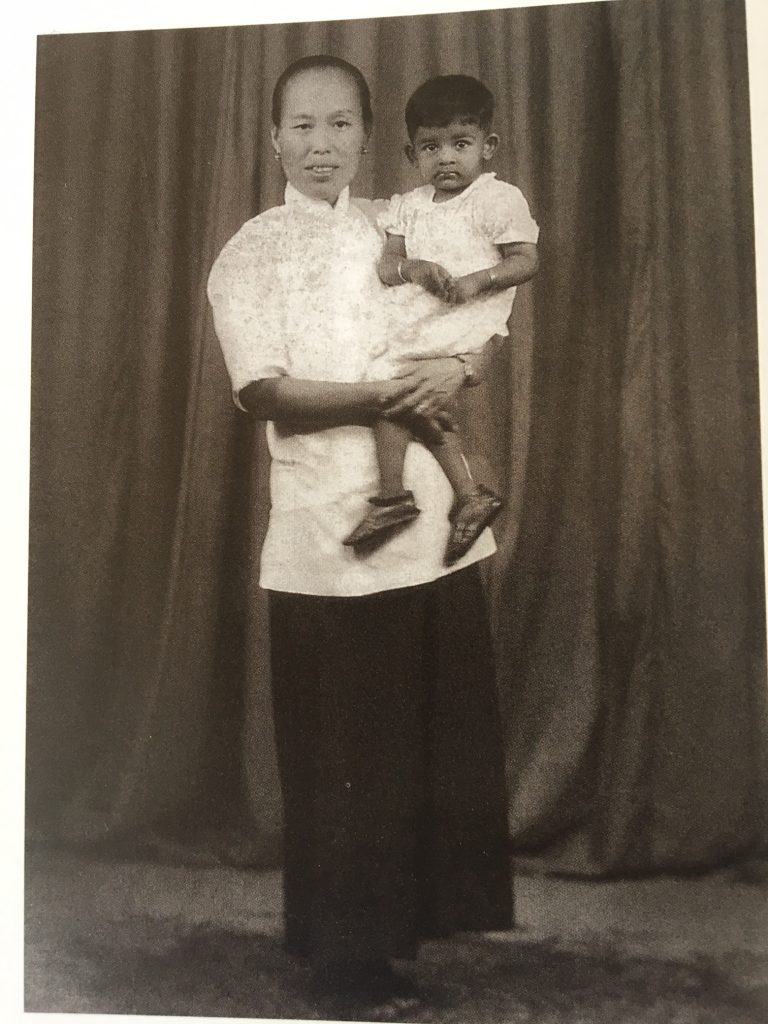

It was at the hospital there that she met Carol’s mother, Sara, who needed help with her wrinkled newborn daughter, Carol. She asked if Kim would return with the family as their amah to Klang, Malaya.

Kim is the strongest of the “dragons” in Dining with Dragons.

“She was a diminutive woman, a poor peasant from the Pearl River who had more innate wisdom and courage than the strongest male I’ve ever met,” says Carol. “She was uneducated yet knew how to behave, to keep secrets and not to harbour any anger or ill feeling towards anyone.”

It was through Kim that the young Carol was introduced to the world of food and cooking.

“I was constantly in her company and watched her when I sat in the kitchen. She taught me to help with basic things like squeezing coconut milk. It was fun.

“My mother didn’t cook. She was a teacher and hated kitchens because she’d had the worst years of her life helping in the orphanage kitchen from the age of three.”

Kim was a good, natural cook blessed with “taste memory”.

“She would look at a dish, smell it and taste and then recreate it. She used to ask me ‘what type of smell do you get in your mouth?’ When I was about eight, I remember her adding an egg to a curry to see if I could identify the taste of egg in my mouth.

“She would add the first ingredient, wait until it was lightly browned, then add another ingredient. Layering food gives each item prominence, whether it be a herb or spice, and the different flavours can be tasted, making the dish unusual and very flavoursome. “The Chinese brought woks to South East Asia,” says Carol. “My amah used a variety of sizes depending on the dish which might be noodles, a stir-fry or a curry or rendang.”

The other dragons in the book are her mother and her friends.

“Quite a few of the women around me were dragons. They breathed fire into my life. They planted a taste sense that eventually flared into my passion for food — its history and culture, my love of cooking and sharing food, treating it as comfort, love and, most of all a heritage to cherish. A few of these dragons have been long gone, but others will recognise themselves here.”

Carol’s mother and her ‘sister-friends’ grew up in a small Methodist orphanage and boarding school in Penang.

“They showed strength and courage as well, achieving far more than girls from rich homes who married and became towkay news (ladies of leisure) whereas the orphans like my Ma, Sara, and women like Aunty Siok and Aunty Poh, went into important careers like teaching and nursing that were needed in the growing economy of Malaya in the early 20th century. They led the way for women in Malaya then.”

Food, says Carol, has always been the binding force in the family. Festivals such as Chinese New Year, the Muslim Hari Raya and the Hindu Deepavali have also helped the family stay connected.

“Such was the easy tolerance of old Malaya that not many people were particular about who was celebrating what – we lived for all the festivals,” says Carol.

When she was six, Carol and her younger brother JoJo travelled with Kim to celebrate Chinese New Year in Singapore. Kim had not seen her brothers for over a decade and she needed their help in getting her teenage children and her mother out of war-torn China.

That trip south taught Carol a great deal about how the past impinges on the present. Kim had prepared delicate rice cakes, Nonya pineapple tarts and pickles to serve at her brother’s home altar which sat high above the dining table, covered with cantilevered red cloth.

On it rested a hand-coloured, faded picture of amah’s father and a tiny faded picture of Chun. “The rituals of Chinese New Year keep people connected,” she says. “Even today, people travel far and wide to be together for the Chinese New Year dinner.

Ancestor worship, which was an important Confucian Chinese observance, stems from the fundamental principle of filial piety.”

Kim’s brother Mr Leung explained to Carol and JoJo some of the traditions of the lunar cycle and the twelve animals that represent each year.

“Chinese do not ask you for your age but which animal zodiac you belong to,” he told them. “Chinese from China are more formal with their celebrations because they are’ FOB’ – fresh off the boat! In fifty years or more, we too will be bending the rules as we grow used to Singapore ways and feel comfortable here.”

After much activity in the kitchen and explanations about the meaning of various new year dishes (fish symbolise “plenty” and prawns “happy laughter”) the family toasted the head of the house, Uncle Leung, who in turn summed up the Chinese philosophy of food for JoJo and Carol.

“Our family is lucky to be here today. We were very poor in China. We learnt not to waste anything in case there was no food tomorrow. You have seen we have learnt to cook even chicken feet and pig’s blood into tasty dishes.

“Let us drink a toast to our family in China. We hope they, too, will be here soon.”

That new year celebration in Singapore with her family turned out to be especially auspicious for Carol’s amah, but you’ll have to read the book to find out more.

A copy of Dining with Dragons can be purchased here

Kim’s brothers had already left China to find work in Sin-Ka-Por (Singapore) and their departure encouraged her to plan her own. Leaving the three children with her mother, she fled to Hong Kong and then to Singapore where she soon found work as an amah (nanny).

It was at the hospital there that she met Carol’s mother, Sara, who needed help with her wrinkled newborn daughter, Carol. She asked if Kim would return with the family as their amah to Klang, Malaya.

Kim is the strongest of the “dragons” in Dining with Dragons.

“She was a diminutive woman, a poor peasant from the Pearl River who had more innate wisdom and courage than the strongest male I’ve ever met,” says Carol. “She was uneducated yet knew how to behave, to keep secrets and not to harbour any anger or ill feeling towards anyone.”

It was through Kim that the young Carol was introduced to the world of food and cooking.

“I was constantly in her company and watched her when I sat in the kitchen. She taught me to help with basic things like squeezing coconut milk. It was fun.

“My mother didn’t cook. She was a teacher and hated kitchens because she’d had the worst years of her life helping in the orphanage kitchen from the age of three.”

Kim was a good, natural cook blessed with “taste memory”.

“She would look at a dish, smell it and taste and then recreate it. She used to ask me ‘what type of smell do you get in your mouth?’ When I was about eight, I remember her adding an egg to a curry to see if I could identify the taste of egg in my mouth.

“She would add the first ingredient, wait until it was lightly browned, then add another ingredient. Layering food gives each item prominence, whether it be a herb or spice, and the different flavours can be tasted, making the dish unusual and very flavoursome. “The Chinese brought woks to South East Asia,” says Carol. “My amah used a variety of sizes depending on the dish which might be noodles, a stir-fry or a curry or rendang.”

The other dragons in the book are her mother and her friends.

“Quite a few of the women around me were dragons. They breathed fire into my life. They planted a taste sense that eventually flared into my passion for food — its history and culture, my love of cooking and sharing food, treating it as comfort, love and, most of all a heritage to cherish. A few of these dragons have been long gone, but others will recognise themselves here.”

Carol’s mother and her ‘sister-friends’ grew up in a small Methodist orphanage and boarding school in Penang.

“They showed strength and courage as well, achieving far more than girls from rich homes who married and became towkay news (ladies of leisure) whereas the orphans like my Ma, Sara, and women like Aunty Siok and Aunty Poh, went into important careers like teaching and nursing that were needed in the growing economy of Malaya in the early 20th century. They led the way for women in Malaya then.”

Food, says Carol, has always been the binding force in the family. Festivals such as Chinese New Year, the Muslim Hari Raya and the Hindu Deepavali have also helped the family stay connected.

“Such was the easy tolerance of old Malaya that not many people were particular about who was celebrating what – we lived for all the festivals,” says Carol.

When she was six, Carol and her younger brother JoJo travelled with Kim to celebrate Chinese New Year in Singapore. Kim had not seen her brothers for over a decade and she needed their help in getting her teenage children and her mother out of war-torn China.

That trip south taught Carol a great deal about how the past impinges on the present. Kim had prepared delicate rice cakes, Nonya pineapple tarts and pickles to serve at her brother’s home altar which sat high above the dining table, covered with cantilevered red cloth.

On it rested a hand-coloured, faded picture of amah’s father and a tiny faded picture of Chun. “The rituals of Chinese New Year keep people connected,” she says. “Even today, people travel far and wide to be together for the Chinese New Year dinner.

Ancestor worship, which was an important Confucian Chinese observance, stems from the fundamental principle of filial piety.”

Kim’s brother Mr Leung explained to Carol and JoJo some of the traditions of the lunar cycle and the twelve animals that represent each year.

“Chinese do not ask you for your age but which animal zodiac you belong to,” he told them. “Chinese from China are more formal with their celebrations because they are’ FOB’ – fresh off the boat! In fifty years or more, we too will be bending the rules as we grow used to Singapore ways and feel comfortable here.”

After much activity in the kitchen and explanations about the meaning of various new year dishes (fish symbolise “plenty” and prawns “happy laughter”) the family toasted the head of the house, Uncle Leung, who in turn summed up the Chinese philosophy of food for JoJo and Carol.

“Our family is lucky to be here today. We were very poor in China. We learnt not to waste anything in case there was no food tomorrow. You have seen we have learnt to cook even chicken feet and pig’s blood into tasty dishes.

“Let us drink a toast to our family in China. We hope they, too, will be here soon.”

That new year celebration in Singapore with her family turned out to be especially auspicious for Carol’s amah, but you’ll have to read the book to find out more.

A copy of Dining with Dragons can be purchased here

Unlike her previous 14 cookbooks, this one is a memoir spanning three generations of family life in Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Canada, the US and Australia.

Food, and her memories associated with the smelling, eating and cooking of it from early childhood through to the present, is a major theme, as is learning from the past.

The book opens with a vivid image of 22-year old Kim bent over a hoong lo (earthen stove) near a bridge construction site on the Pearl River, Canton, in 1924. Kim’s husband Chun is one of the bridge-builders and they have a 5 year old boy and 3 year old daughter with another on the way.

“Kim squatted close to the steaming pot and, with long handled chopsticks, drew out a few grains of rice from the chuk (rice congee) she was cooking. She tested the grains, then dragged a wooden bucket closer, scraped the bottom of the pot, and dropped in a handful of chopped vegetables and some damp rock salt. A few drops of soy sauce or precious sesame oil, added just before eating, would finish it. There were no more dried prawns and rendered pork, but the bridge was nearing completion and Chun would be paid. In the meantime, plain congee would have to do.”

Chun never returned from work that day. Part of the bridge collapsed, killing him as it fell.

Having married Chun, Kim now belonged to his family and was considered as nothing but chattel. Her mother-in-law treated her cruelly, blaming Kim for Chun’s death while her bothers-in-law made it clear she would be used as a concubine once her third child was born. Like many Chinese women at that time, Kim risked being condemned to oppression for life because of her gender.

But Kim remembered something her mother had told her, something whispered into her tiny ear to guide her through life in the lucky year of the dragon.

“Be strong like the dragon. You will be the salt of life, nui tsai – girl child.”

Unlike her previous 14 cookbooks, this one is a memoir spanning three generations of family life in Sri Lanka, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Canada, the US and Australia.

Food, and her memories associated with the smelling, eating and cooking of it from early childhood through to the present, is a major theme, as is learning from the past.

The book opens with a vivid image of 22-year old Kim bent over a hoong lo (earthen stove) near a bridge construction site on the Pearl River, Canton, in 1924. Kim’s husband Chun is one of the bridge-builders and they have a 5 year old boy and 3 year old daughter with another on the way.

“Kim squatted close to the steaming pot and, with long handled chopsticks, drew out a few grains of rice from the chuk (rice congee) she was cooking. She tested the grains, then dragged a wooden bucket closer, scraped the bottom of the pot, and dropped in a handful of chopped vegetables and some damp rock salt. A few drops of soy sauce or precious sesame oil, added just before eating, would finish it. There were no more dried prawns and rendered pork, but the bridge was nearing completion and Chun would be paid. In the meantime, plain congee would have to do.”

Chun never returned from work that day. Part of the bridge collapsed, killing him as it fell.

Having married Chun, Kim now belonged to his family and was considered as nothing but chattel. Her mother-in-law treated her cruelly, blaming Kim for Chun’s death while her bothers-in-law made it clear she would be used as a concubine once her third child was born. Like many Chinese women at that time, Kim risked being condemned to oppression for life because of her gender.

But Kim remembered something her mother had told her, something whispered into her tiny ear to guide her through life in the lucky year of the dragon.

“Be strong like the dragon. You will be the salt of life, nui tsai – girl child.” Kim’s brothers had already left China to find work in Sin-Ka-Por (Singapore) and their departure encouraged her to plan her own. Leaving the three children with her mother, she fled to Hong Kong and then to Singapore where she soon found work as an amah (nanny).

It was at the hospital there that she met Carol’s mother, Sara, who needed help with her wrinkled newborn daughter, Carol. She asked if Kim would return with the family as their amah to Klang, Malaya.

Kim is the strongest of the “dragons” in Dining with Dragons.

“She was a diminutive woman, a poor peasant from the Pearl River who had more innate wisdom and courage than the strongest male I’ve ever met,” says Carol. “She was uneducated yet knew how to behave, to keep secrets and not to harbour any anger or ill feeling towards anyone.”

It was through Kim that the young Carol was introduced to the world of food and cooking.

“I was constantly in her company and watched her when I sat in the kitchen. She taught me to help with basic things like squeezing coconut milk. It was fun.

“My mother didn’t cook. She was a teacher and hated kitchens because she’d had the worst years of her life helping in the orphanage kitchen from the age of three.”

Kim was a good, natural cook blessed with “taste memory”.

“She would look at a dish, smell it and taste and then recreate it. She used to ask me ‘what type of smell do you get in your mouth?’ When I was about eight, I remember her adding an egg to a curry to see if I could identify the taste of egg in my mouth.

“She would add the first ingredient, wait until it was lightly browned, then add another ingredient. Layering food gives each item prominence, whether it be a herb or spice, and the different flavours can be tasted, making the dish unusual and very flavoursome. “The Chinese brought woks to South East Asia,” says Carol. “My amah used a variety of sizes depending on the dish which might be noodles, a stir-fry or a curry or rendang.”

The other dragons in the book are her mother and her friends.

“Quite a few of the women around me were dragons. They breathed fire into my life. They planted a taste sense that eventually flared into my passion for food — its history and culture, my love of cooking and sharing food, treating it as comfort, love and, most of all a heritage to cherish. A few of these dragons have been long gone, but others will recognise themselves here.”

Carol’s mother and her ‘sister-friends’ grew up in a small Methodist orphanage and boarding school in Penang.

“They showed strength and courage as well, achieving far more than girls from rich homes who married and became towkay news (ladies of leisure) whereas the orphans like my Ma, Sara, and women like Aunty Siok and Aunty Poh, went into important careers like teaching and nursing that were needed in the growing economy of Malaya in the early 20th century. They led the way for women in Malaya then.”

Food, says Carol, has always been the binding force in the family. Festivals such as Chinese New Year, the Muslim Hari Raya and the Hindu Deepavali have also helped the family stay connected.

“Such was the easy tolerance of old Malaya that not many people were particular about who was celebrating what – we lived for all the festivals,” says Carol.

When she was six, Carol and her younger brother JoJo travelled with Kim to celebrate Chinese New Year in Singapore. Kim had not seen her brothers for over a decade and she needed their help in getting her teenage children and her mother out of war-torn China.

That trip south taught Carol a great deal about how the past impinges on the present. Kim had prepared delicate rice cakes, Nonya pineapple tarts and pickles to serve at her brother’s home altar which sat high above the dining table, covered with cantilevered red cloth.

On it rested a hand-coloured, faded picture of amah’s father and a tiny faded picture of Chun. “The rituals of Chinese New Year keep people connected,” she says. “Even today, people travel far and wide to be together for the Chinese New Year dinner.

Ancestor worship, which was an important Confucian Chinese observance, stems from the fundamental principle of filial piety.”

Kim’s brother Mr Leung explained to Carol and JoJo some of the traditions of the lunar cycle and the twelve animals that represent each year.

“Chinese do not ask you for your age but which animal zodiac you belong to,” he told them. “Chinese from China are more formal with their celebrations because they are’ FOB’ – fresh off the boat! In fifty years or more, we too will be bending the rules as we grow used to Singapore ways and feel comfortable here.”

After much activity in the kitchen and explanations about the meaning of various new year dishes (fish symbolise “plenty” and prawns “happy laughter”) the family toasted the head of the house, Uncle Leung, who in turn summed up the Chinese philosophy of food for JoJo and Carol.

“Our family is lucky to be here today. We were very poor in China. We learnt not to waste anything in case there was no food tomorrow. You have seen we have learnt to cook even chicken feet and pig’s blood into tasty dishes.

“Let us drink a toast to our family in China. We hope they, too, will be here soon.”

That new year celebration in Singapore with her family turned out to be especially auspicious for Carol’s amah, but you’ll have to read the book to find out more.

A copy of Dining with Dragons can be purchased here

Kim’s brothers had already left China to find work in Sin-Ka-Por (Singapore) and their departure encouraged her to plan her own. Leaving the three children with her mother, she fled to Hong Kong and then to Singapore where she soon found work as an amah (nanny).

It was at the hospital there that she met Carol’s mother, Sara, who needed help with her wrinkled newborn daughter, Carol. She asked if Kim would return with the family as their amah to Klang, Malaya.

Kim is the strongest of the “dragons” in Dining with Dragons.

“She was a diminutive woman, a poor peasant from the Pearl River who had more innate wisdom and courage than the strongest male I’ve ever met,” says Carol. “She was uneducated yet knew how to behave, to keep secrets and not to harbour any anger or ill feeling towards anyone.”

It was through Kim that the young Carol was introduced to the world of food and cooking.

“I was constantly in her company and watched her when I sat in the kitchen. She taught me to help with basic things like squeezing coconut milk. It was fun.

“My mother didn’t cook. She was a teacher and hated kitchens because she’d had the worst years of her life helping in the orphanage kitchen from the age of three.”

Kim was a good, natural cook blessed with “taste memory”.

“She would look at a dish, smell it and taste and then recreate it. She used to ask me ‘what type of smell do you get in your mouth?’ When I was about eight, I remember her adding an egg to a curry to see if I could identify the taste of egg in my mouth.

“She would add the first ingredient, wait until it was lightly browned, then add another ingredient. Layering food gives each item prominence, whether it be a herb or spice, and the different flavours can be tasted, making the dish unusual and very flavoursome. “The Chinese brought woks to South East Asia,” says Carol. “My amah used a variety of sizes depending on the dish which might be noodles, a stir-fry or a curry or rendang.”

The other dragons in the book are her mother and her friends.

“Quite a few of the women around me were dragons. They breathed fire into my life. They planted a taste sense that eventually flared into my passion for food — its history and culture, my love of cooking and sharing food, treating it as comfort, love and, most of all a heritage to cherish. A few of these dragons have been long gone, but others will recognise themselves here.”

Carol’s mother and her ‘sister-friends’ grew up in a small Methodist orphanage and boarding school in Penang.

“They showed strength and courage as well, achieving far more than girls from rich homes who married and became towkay news (ladies of leisure) whereas the orphans like my Ma, Sara, and women like Aunty Siok and Aunty Poh, went into important careers like teaching and nursing that were needed in the growing economy of Malaya in the early 20th century. They led the way for women in Malaya then.”

Food, says Carol, has always been the binding force in the family. Festivals such as Chinese New Year, the Muslim Hari Raya and the Hindu Deepavali have also helped the family stay connected.

“Such was the easy tolerance of old Malaya that not many people were particular about who was celebrating what – we lived for all the festivals,” says Carol.

When she was six, Carol and her younger brother JoJo travelled with Kim to celebrate Chinese New Year in Singapore. Kim had not seen her brothers for over a decade and she needed their help in getting her teenage children and her mother out of war-torn China.

That trip south taught Carol a great deal about how the past impinges on the present. Kim had prepared delicate rice cakes, Nonya pineapple tarts and pickles to serve at her brother’s home altar which sat high above the dining table, covered with cantilevered red cloth.

On it rested a hand-coloured, faded picture of amah’s father and a tiny faded picture of Chun. “The rituals of Chinese New Year keep people connected,” she says. “Even today, people travel far and wide to be together for the Chinese New Year dinner.

Ancestor worship, which was an important Confucian Chinese observance, stems from the fundamental principle of filial piety.”

Kim’s brother Mr Leung explained to Carol and JoJo some of the traditions of the lunar cycle and the twelve animals that represent each year.

“Chinese do not ask you for your age but which animal zodiac you belong to,” he told them. “Chinese from China are more formal with their celebrations because they are’ FOB’ – fresh off the boat! In fifty years or more, we too will be bending the rules as we grow used to Singapore ways and feel comfortable here.”

After much activity in the kitchen and explanations about the meaning of various new year dishes (fish symbolise “plenty” and prawns “happy laughter”) the family toasted the head of the house, Uncle Leung, who in turn summed up the Chinese philosophy of food for JoJo and Carol.

“Our family is lucky to be here today. We were very poor in China. We learnt not to waste anything in case there was no food tomorrow. You have seen we have learnt to cook even chicken feet and pig’s blood into tasty dishes.

“Let us drink a toast to our family in China. We hope they, too, will be here soon.”

That new year celebration in Singapore with her family turned out to be especially auspicious for Carol’s amah, but you’ll have to read the book to find out more.

A copy of Dining with Dragons can be purchased here

What a wonderful story! Must find and read a copy of the book.

Thank you for this wonderful article!

Thanks Mercedes, it’s a fascinating book. You should be able to purchase a copy direct from Carol her: https://carolselvarajah.com.au/dining-with-dragons/

cheers,

Sheridan

Thank you so much, Sheridan. The book has been ordered and I am eagerly waiting on deliver from overseas.

Great! thanks for your feedback, Mercedes.