A walk Around the Dyarubbin

It’s a good hour’s drive north-west of Sydney to Produce By The River, the Muscat family farm at Pitt Town Bottoms, not far from the historic town of Windsor on the Hawkesbury River.

I’ve come to visit some of the local farmers and to find out more about the history of the River Dyarubbin, the local Darug name for the Hawkesbury.

I’m welcomed by William Muscat, youngest son of Jim and Rita who have grown veggies in the area since the late 1970s. We first met at Carriageworks Farmers Market one Saturday morning when Willy and his brother Andrew were busily serving a queue of keen customers tempted by the attractive display of produce.

The brothers’ farm lies on 20 acres of fertile river plain. Looking out across neat rows of kale, chicory, daikon, spinach and fennel toward the large green shed on the other side of the road, I see striated dark black lines high up along the side.

“The March flood went into the sheds,” explains Willy. “We’re 10m above sea level here and the river rose to 14m. We have to pull up the pumps as soon as the flood starts and move all the equipment up the hill which is18m above sea level.”

“The April flood was moderate, about 9m, and flooded half the farm but didn’t go into the sheds.”

The brothers have been growing veggies here for the past 20 years and this has been the longest wet season since they started.

“We’ve had two major and two minor floods in the past 3 years. The river here is tidal and rises rapidly when the gates at Warragamba Dam are opened. The floods have altered the river banks. The 13.4m flood in March last year brought in a lot of silt but this year there was a lot more silt down river at Ebenezer.”

When I visited, Rita was sitting inside one of the sheds sorting cucumbers and zucchini and Jim was manoeuvring a bobcat. The family do all the work themselves and cannot afford the annual flood insurance of $100,000.

“The flood finished off our tomatoes and took away one of our demountables and a large plastic water tank. The soil hasn’t had time to dry out so planting has slowed up for a few weeks.”

Black plastic has been laid to control the weeds which also helps keep the ground warm. The soil is prepared with a rotary hoer and bed shaper and fertilised with pelleted fertiliser.

The Muscats are survivors. Fortunately they’ve been given a helping hand by other local growers who fill gaps in their market produce.

Just as I’m about to leave, a flock of cockatoos fly overhead, screeching loudly. “A sign of rain coming,” says Willy wryly.

Driving back along the road to Windsor I’m struck by farm after farm of perfect flat green turf.

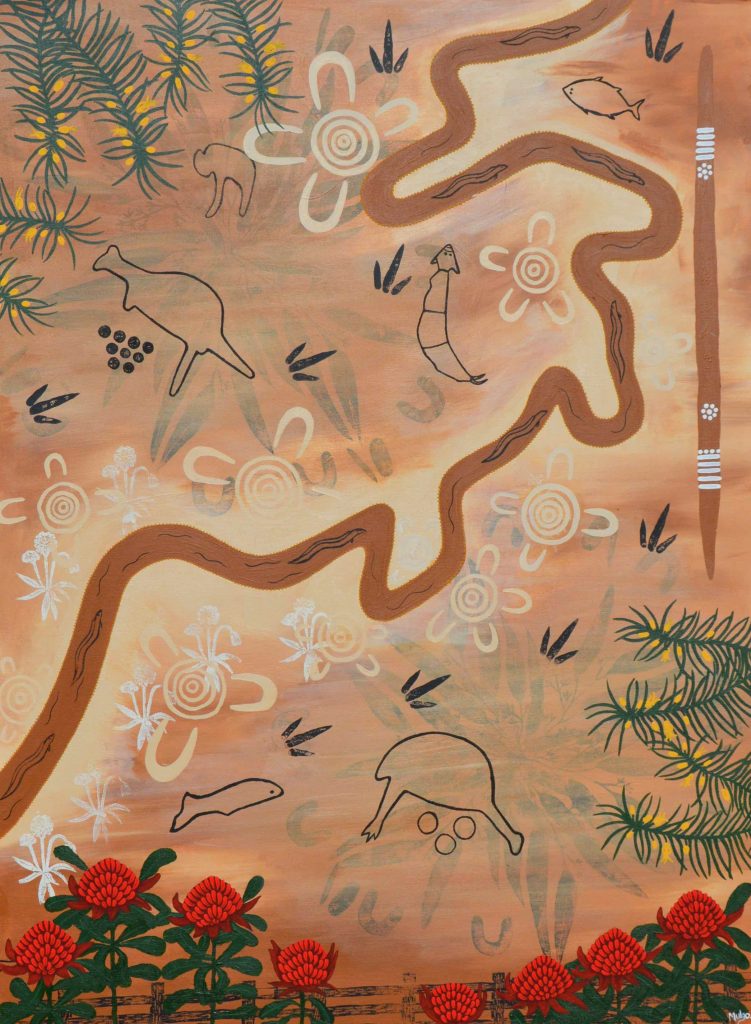

I’ve been invited to the opening of 11 Stories from the River Dyarubbin at the Hawkesbury Regional Museum in Windsor, a collaborative public art work comprising a series of audio walks which bring together a wide range of people telling stories about the river accompanied by original music by producer/composer Ooonagh Sherrard.

Here I discover that the turf industry is the largest in the country boasting 25% of national production with a wholesale value of $70m annually.

“The area used to be Sydney’s food bowl, now it is mostly turf,” says Oonagh.

“The interesting thing for me after hearing all the historic interviews is that during the 1960s and 1990s many farmers turned away from veggies and fruit because the effects of flooding were too devastating.

“We’ve had about a 30 year dry period so these affects have not been felt for a while.”

Jen Dollin, Head of Sustainability Education, Western Sydney University, and one of many experts interviewed for the project points to the importance of native vegetation along the river bank which creates a micro world of trees, plants, undergrowth and insects.

“What we do on the banks of the river impacts what’s in the river. It’s a whole systemic integration rather than just thinking about the river as a strip of water.”

She says that while there’s legislation in place, the will to actually enforce it and push it through doesn’t exist within local council because they’re exhausted and under-resourced.

“If you look at the EPA which is the monitoring body, it’s a fractured system of policy and legislative dysfunction.

“This is the most incredible river system, I believe, in Australia. Let’s get this right.”

Sue Cusbert, technical officer from Western Sydney University talks about how she has been testing the water for over 30 years. “While it is less polluted now, turbidity caused by housing developments and turf farm run-off is a huge problem. These are flood plains with beautiful soil.

“I find it a real shame that grass is worth more for a farmer to grow than food and I think that says a lot for society.”

The first wharf built at Windsor in 1795 was washed away, something the early settlers acknowledged Aboriginal people knew was coming followed by 27 major floods during the 19th century.

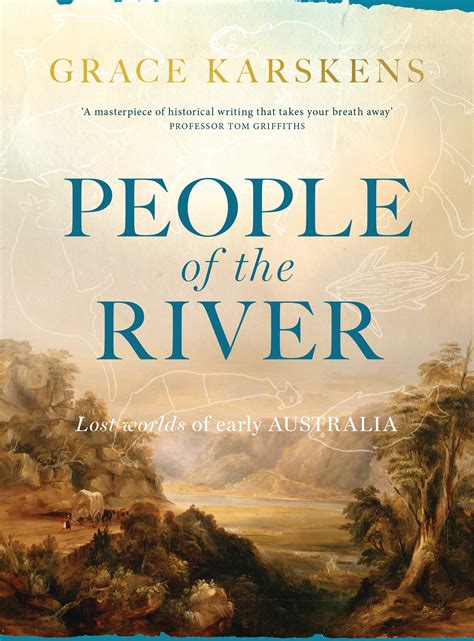

I listen to historian Grace Karskens, author of the outstanding People of the River, who says that flood history is very much part of the Hawkesbury story for both peoples.

“One of the largest occurred in March 1806, not long after early settlers had begun to celebrate the area as a regular food source,” says Karskens.

“To have this flood go through and wreck everything came at the wrong time and washed away all the wheat and corn that had been harvested. They were terrified there’d be a food shortage. Governor King was really concerned and wanted to to know if it was going to happen again so they asked the Aboriginal people.”

I continue around the river to meet Rhiannon Phillips, manager of Happy Farm, a regenerative, certified organic farm at North Richmond. The veggie farm is located at the bottom of a hill overlooking the river. As I walk down the hill, I’m overcome by the beauty of the landscape and fertility of the river plain.

“The recent flood killed our sunflowers and swept away some of the veggies but we bounced back quite quickly once it was dry enough to get in,” says Rhiannon.

She shows me long healthy rows of fennel interplanted with leeks, wombok interplanted with spring onions, kohlrabi with coriander and bok choy, daikon radish with stringless beans. Interplanting helps cover the soil and prevent weeds.

“There were a lot of weeds after the floods where the water settled,” she says. “We either pull them out by hand or use weed gunnel. It’s predominantly a no-till garden. Tilling the soil releases carbon which we’re trying to store.”

Down in a gully on the other side of the hill, a syntropic food forest has been planted by Scott Hall.

“It’s a mix of permaculture, agroforestry and companion planting and creates its own eco-system. It was planted two years ago and will begin to pay for itself in another couple of years,” she explains.

She tells me it’s taken a while to get used to this style of farming because she’s mostly worked in conventional agriculture.

“The agriculture industry needs to move away from the use of chemicals and synthetic fertilisers and towards a way of farming which mimics the natural environment.

“How will conventional farmers manage as the price of diesel and chemical accelerates? Holistic management, including animals is, for me, the way forward on this property.”

Collaborating with the local community is also high on her list. Happy Farm supplies a number of local restaurants with veggies and recently teamed up with The Royal Richmond Hotel. Starting in July, they’re offering 9 -12 varieties of fresh local, organic seasonal veggies in plastic-free compostable boxes to 30 -50 subscribers.

Jo Ward, chef at the Royal Richmond, has been busily making preserves with produce from Happy Farm and other local farms including Block 11 Organics, Mountain Lagoon Orchard and Bilpin Blossom Farm. Her Block 11 Peach & Fermented Chilli Hot Sauce and Fig Jam are sensational.

Block 11 sell produce boxes through their website and a range veggies on Saturdays at Carriageworks. I bumped into owner Greg Kocanda there recently who told me that it’s the timing and length of the recent floods that has affected veggie farmers along the river.

“We’re going into winter now with shorter days and lower temperatures and the soil isn’t drying out. It was never going to be a great season.”

Family-owned and operated since 1939, what keeps farmers like the Kocandas going is an unlimited supply of water and seven metres of fertile topsoil along the river bank.

“We’ll go again,” he tells me cheerfully.

Ooonagh Sherrard, producer of 11 Stories from the River Dyarubbin, alerts me to a forum organised last week by Western Sydney University which appointed a riverkeeper for the river, “a voice – a small step towards rights for the river…”

“A few years ago, when flying into Sydney from the north, the plane circled around and around over the lower Hawkesbury river,” she adds.

“In that moment I looked down over the river at the most beautiful place I had ever seen, like a bird soaring over the Country I grew up in.

“My heart spoke to me loudly and I knew that I needed to make time for a project I had dreamed of making – to inspire love and care for the river Country,” she says.

So informative and interesting an article On these market gardeners as they prevail in spite of continual floods. The turf farms seem to be

The only ones reasonably sure of a steady income and have the natural advantage of water and the replenishment of regular silt which costs them nothing.

To have those growing such great fresh produce close by is a boon to good living in the city and so very welcome. Long may they continue.

Thank you for your comment, I take my hat off to those farmers who persist growing veggies on the flood plain.

Sydney needs farmers in close proximity to the city to offset increasing problems with food insecurity. Long live the market gardeners supplying Sydney!

Sheridan

3 devastating floods are just going to be a flood too far for some some of these indie local farms. Happy farms was supplying the Royal Windsor with fresh veggies, they’ve created a kitchen and have a fab chef that can create good food from what has ripened and freshly harvested. Yet I understand that for happy farms it is simply a flood to far. They are not going to rebuild their veggie field. Ongoing local employment, local business and importantly a field not growing some delicious fruit and vegies . Farms like Happy Farms farming practices help build the soil fertility for generations to come . These are not usual floods hitting our farms. These deposit debris mud and slit and rubbish They drown some of the crops. That can take years to recover if ever. Sheridan’s article is a picture captured of an area in recovery. And sadly Happy Farms is unable to withstand this continuous battering.

Thanks for your concern, Catriona. It’s so sad that Happy Farms will close after this recent devastating flood. I hope other farmers along the river bank manage to recover quickly. Sheridan