Winter Solstice in Hobart

Tasmania will always be the apple isle for me. No matter that these days it boasts all manner of fabulous gourmet foods: fresh truffles, wasabi, cheeses, saffron, wild abalone, rock lobsters and sea urchins.

Nor is it because the shape of this pristine green isle summons up an apple image.

It’s more personal than that.

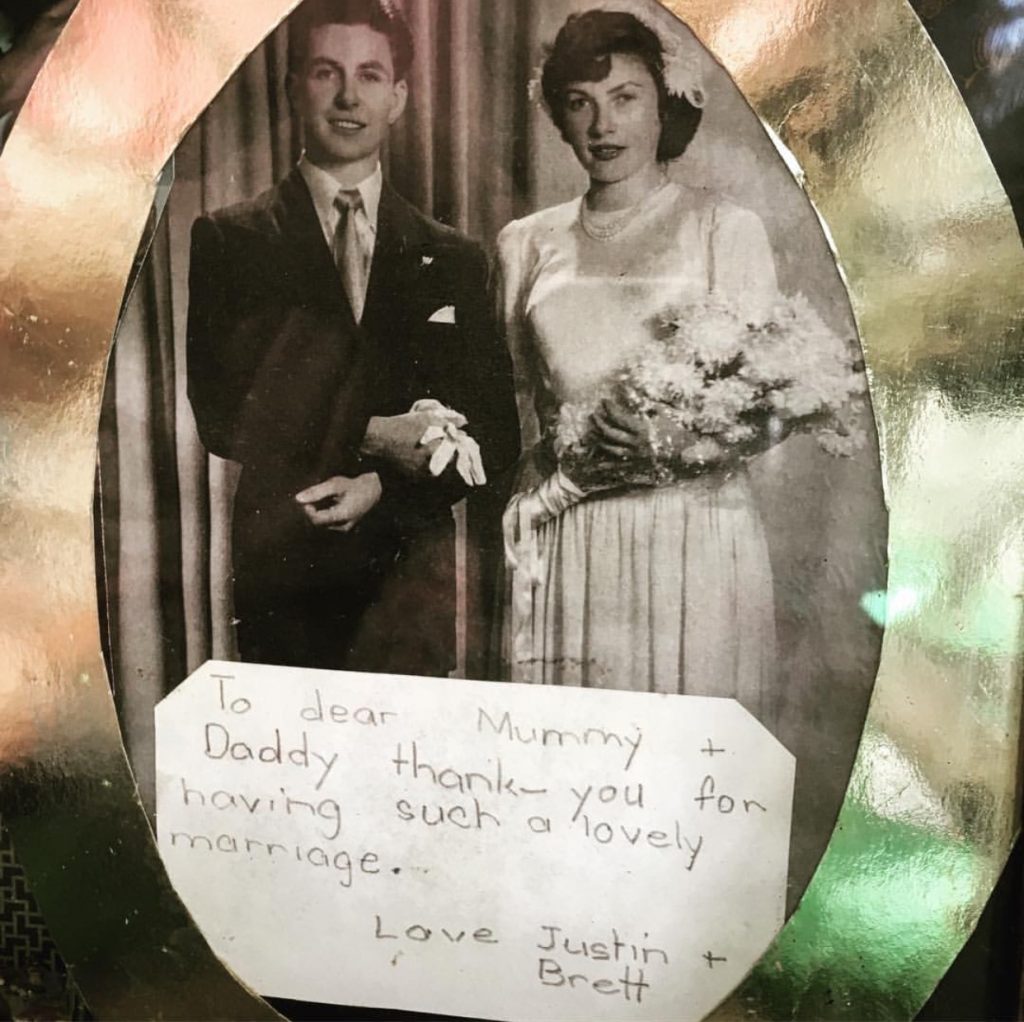

Tasmania, specifically Hobart, is part of my family history. It’s where my parents met and married on June 13th, 1949, at what was then the Wrest Point Riviera Hotel overlooking the Derwent River in Sandy Bay. Built during WW2 by Arthur Drysdale, an enterprising local entrepreneur, it quickly became “the place to be seen”.

Arriving by ship from Brisbane, my mother first found work picking raspberries at Molesworth, 40 minutes by car north-west of Hobart (Molesworth is where Sally Wise, renowned for her books on bottling and preserves, now runs a cooking school).

For the first few weeks she lived on a farm, with her friend Daphne White, in a wooden hut where there was no running water or electricity .

Apparently they both had great fun there, though all her life my mother has complained of cold weather.

Being such good lookers, it didn’t take them long to find work as waitresses at the swish new hotel.

At the time, my father was working as an announcer for the local ABC radio station playing classical music. A mutual friend, Sandy Morton, introduced them. It was love at first sight. She was 18, he was 22.

Over the years she has often commented on the lovely red cheeks he had when they first met.

“As rosy as a Huon Valley apple!” she declares (my mother also loves baked apples – you’ll find a recipe here).

In her charming book, A Table In The Orchard, Michelle Crawford points out that the Huon Valley was once the jewel in the crown of Tasmania’s Apple Empire.

“For over a hundred years, thousands of acres of orchards graced the landscape of the island. In the 1950s, nearly two million tonnes of apples were produced in Tasmania each year largely for export to Britain and the rest of Europe…But when Britain joined the Common Market (now the European Union) in the 1970s it effectively turned its back on Australian produce.”

Now that the Brits have voted to leave the Union, the future of the valley might be rosy once again.

On a recent trip to Hobart, I stayed with Margaretta Pos, a family friend, at her home in Battery Point which overlooks the very spot where my parents met. Margaretta is former arts editor of The Mercury newspaper, and also of two fascinating books: Mrs Fenton’s Journey: India and Tasmania 1826-1876 and Shadows in Suriname.

Each morning as I pulled up the blinds and looked out over the calm surface of the river flushed pink from the rising sun, I’d muse on their long, often volatile, marriage and also try to mentally prepare myself to swim in its icy waters on the last day of the Dark Mofo festival.

Over the past five years, plunging into the Derwent after the longest night of the year has become something of a ritual. For some, it’s a way of washing off the excesses of Dark Mofo, for others a way of marking the shortest day of the year.

For me, it was a challenge, something I envisaged as a second baptism. Crazy, yes, but very exhilarating, even though I couldn’t find my towel afterward (the organisers had supplied towels for the 1000 people who’d registered, but scores more had turned up).

I now have a red swimmers cap with “turn the other cheek” scrawled along one side to prove it.

But perhaps even more crazy was the ogoh ogoh parade.

Margaretta had mentioned the parade to me a few times during the week, but given the number of events on at the Dark Mofo festival, I’d forgotten, and had also been too embarrassed to ask her what ogoh ogoh meant.

I knew she was excited about it but had no idea what to expect apart from the fact it would be cold and dark outside.

As I ran down the hill from Battery Point to meet her, the eerie sounds of a Siren Song swirled around me, a sound work played for a few minutes from a hovering helicopter and hundreds of speakers every day during Dark Mofo at dawn and dusk.

A large crowd had already gathered along Salamanca Place and around the piers. I arrived just in time and could hear rhythmic drum beats, chanting voices and clashing pots and pans in the distance.

The procession was under way.

Suddenly the crowd parted to make way for a massive papier-mâché and plaster black bull with enormous white teeth, curved horns, red lips and a red snout which was being carried on a bamboo platform by a dozen or so people.

A large crowd had already gathered along Salamanca Place and around the piers. I arrived just in time and could hear rhythmic drum beats, chanting voices and clashing pots and pans in the distance.

The procession was under way.

Suddenly the crowd parted to make way for a massive papier-mâché and plaster black bull with enormous white teeth, curved horns, red lips and a red snout which was being carried on a bamboo platform by a dozen or so people.  “That’s an ogoh ogoh,” yelled Margaretta into my ear. “It’s a demon-like sculpture common to Balinese Hinduism. The idea is to scare off evil spirits by making unbearable amounts of noise as is humanly possible.”

It was followed soon after by a huge she-devil with large red breasts and belly, long white eye-teeth, menacing face and much jeering and noise.

The enthusiastic chanting and dancing of the crowd was infectious and, as we proceeded along the waterfront towards Dark Park, I began to move in time with the beat. By the time we reached the gates to the park, the procession had slowed almost to a halt to allow the scary creatures on floats room to pass through.

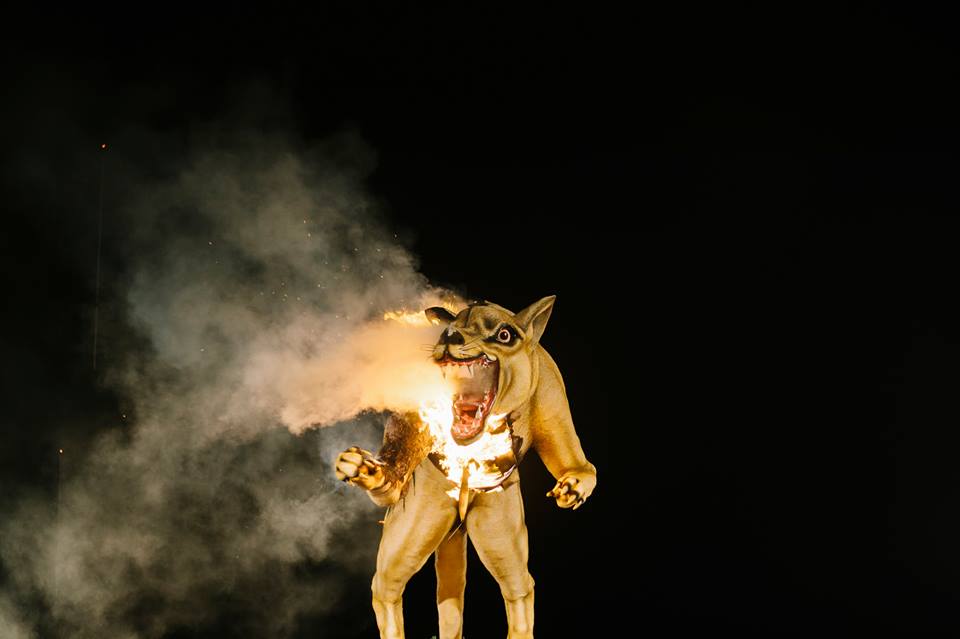

The very last was a long Tasmanian tiger (or Thylacine), a fabled creature with scowling face, bared teeth and long red tongue which was carried into the centre of the park where he was cremated in ceremonial smoke, fire and noise.

In Bali, the burning of the ogoh-ogoh symbolises the eradication of any evil influences in life and is followed by more dancing, drinking and feasting in a rather chaotic fashion, all with the aim of driving evil spirits far away.

I found out later that during the first week of Dark Mofo, festival-goers had been invited to write down their fears and pin them to the tiger, the idea being to give voice to one’s deepest, darkest fears and have them burnt along with the tiger.

As with most of the events I attended at Dark Mofo, the sense of camaraderie amongst the crowd at the ogoh ogoh parade was palpable, and I was really impressed by how well-organised it was.

Last year, creative director of the festival, Leigh Carmichael, pointed out that the partnership with Indonesia was a big step towards Dark Mofo’s vision of “becoming the iconic Australian winter festival”.

“The next phase for us is to build deep and meaningful cross-cultural exchange programs with other countries, like the very strong one we’ve started here with the Indonesian government,” he told The Mercury newspaper.

As I stood there, watching the tiger burn, I thought of my young “just-married” parents and how incomprehensible such a festival would have been to them all those decades ago, of how they’d never have dreamt of fresh salmon, truffles, saffron or wasabi – and of how Dark Mofo’s future is looking very rosy indeed.

“That’s an ogoh ogoh,” yelled Margaretta into my ear. “It’s a demon-like sculpture common to Balinese Hinduism. The idea is to scare off evil spirits by making unbearable amounts of noise as is humanly possible.”

It was followed soon after by a huge she-devil with large red breasts and belly, long white eye-teeth, menacing face and much jeering and noise.

The enthusiastic chanting and dancing of the crowd was infectious and, as we proceeded along the waterfront towards Dark Park, I began to move in time with the beat. By the time we reached the gates to the park, the procession had slowed almost to a halt to allow the scary creatures on floats room to pass through.

The very last was a long Tasmanian tiger (or Thylacine), a fabled creature with scowling face, bared teeth and long red tongue which was carried into the centre of the park where he was cremated in ceremonial smoke, fire and noise.

In Bali, the burning of the ogoh-ogoh symbolises the eradication of any evil influences in life and is followed by more dancing, drinking and feasting in a rather chaotic fashion, all with the aim of driving evil spirits far away.

I found out later that during the first week of Dark Mofo, festival-goers had been invited to write down their fears and pin them to the tiger, the idea being to give voice to one’s deepest, darkest fears and have them burnt along with the tiger.

As with most of the events I attended at Dark Mofo, the sense of camaraderie amongst the crowd at the ogoh ogoh parade was palpable, and I was really impressed by how well-organised it was.

Last year, creative director of the festival, Leigh Carmichael, pointed out that the partnership with Indonesia was a big step towards Dark Mofo’s vision of “becoming the iconic Australian winter festival”.

“The next phase for us is to build deep and meaningful cross-cultural exchange programs with other countries, like the very strong one we’ve started here with the Indonesian government,” he told The Mercury newspaper.

As I stood there, watching the tiger burn, I thought of my young “just-married” parents and how incomprehensible such a festival would have been to them all those decades ago, of how they’d never have dreamt of fresh salmon, truffles, saffron or wasabi – and of how Dark Mofo’s future is looking very rosy indeed.

Flight of the Siren Song helicopter which stops the city in its tracks for 7 minutes at dawn and dusk – it reminded me of the call of the muezzin

“That’s an ogoh ogoh,” yelled Margaretta into my ear. “It’s a demon-like sculpture common to Balinese Hinduism. The idea is to scare off evil spirits by making unbearable amounts of noise as is humanly possible.”

It was followed soon after by a huge she-devil with large red breasts and belly, long white eye-teeth, menacing face and much jeering and noise.

The enthusiastic chanting and dancing of the crowd was infectious and, as we proceeded along the waterfront towards Dark Park, I began to move in time with the beat. By the time we reached the gates to the park, the procession had slowed almost to a halt to allow the scary creatures on floats room to pass through.

The very last was a long Tasmanian tiger (or Thylacine), a fabled creature with scowling face, bared teeth and long red tongue which was carried into the centre of the park where he was cremated in ceremonial smoke, fire and noise.

In Bali, the burning of the ogoh-ogoh symbolises the eradication of any evil influences in life and is followed by more dancing, drinking and feasting in a rather chaotic fashion, all with the aim of driving evil spirits far away.

I found out later that during the first week of Dark Mofo, festival-goers had been invited to write down their fears and pin them to the tiger, the idea being to give voice to one’s deepest, darkest fears and have them burnt along with the tiger.

As with most of the events I attended at Dark Mofo, the sense of camaraderie amongst the crowd at the ogoh ogoh parade was palpable, and I was really impressed by how well-organised it was.

Last year, creative director of the festival, Leigh Carmichael, pointed out that the partnership with Indonesia was a big step towards Dark Mofo’s vision of “becoming the iconic Australian winter festival”.

“The next phase for us is to build deep and meaningful cross-cultural exchange programs with other countries, like the very strong one we’ve started here with the Indonesian government,” he told The Mercury newspaper.

As I stood there, watching the tiger burn, I thought of my young “just-married” parents and how incomprehensible such a festival would have been to them all those decades ago, of how they’d never have dreamt of fresh salmon, truffles, saffron or wasabi – and of how Dark Mofo’s future is looking very rosy indeed.

“That’s an ogoh ogoh,” yelled Margaretta into my ear. “It’s a demon-like sculpture common to Balinese Hinduism. The idea is to scare off evil spirits by making unbearable amounts of noise as is humanly possible.”

It was followed soon after by a huge she-devil with large red breasts and belly, long white eye-teeth, menacing face and much jeering and noise.

The enthusiastic chanting and dancing of the crowd was infectious and, as we proceeded along the waterfront towards Dark Park, I began to move in time with the beat. By the time we reached the gates to the park, the procession had slowed almost to a halt to allow the scary creatures on floats room to pass through.

The very last was a long Tasmanian tiger (or Thylacine), a fabled creature with scowling face, bared teeth and long red tongue which was carried into the centre of the park where he was cremated in ceremonial smoke, fire and noise.

In Bali, the burning of the ogoh-ogoh symbolises the eradication of any evil influences in life and is followed by more dancing, drinking and feasting in a rather chaotic fashion, all with the aim of driving evil spirits far away.

I found out later that during the first week of Dark Mofo, festival-goers had been invited to write down their fears and pin them to the tiger, the idea being to give voice to one’s deepest, darkest fears and have them burnt along with the tiger.

As with most of the events I attended at Dark Mofo, the sense of camaraderie amongst the crowd at the ogoh ogoh parade was palpable, and I was really impressed by how well-organised it was.

Last year, creative director of the festival, Leigh Carmichael, pointed out that the partnership with Indonesia was a big step towards Dark Mofo’s vision of “becoming the iconic Australian winter festival”.

“The next phase for us is to build deep and meaningful cross-cultural exchange programs with other countries, like the very strong one we’ve started here with the Indonesian government,” he told The Mercury newspaper.

As I stood there, watching the tiger burn, I thought of my young “just-married” parents and how incomprehensible such a festival would have been to them all those decades ago, of how they’d never have dreamt of fresh salmon, truffles, saffron or wasabi – and of how Dark Mofo’s future is looking very rosy indeed.